In 1967, “The Wincanton Report,” a federally funded study, was published about corruption and organized crime in a small city. Wincanton, a fictional name chosen to protect innocent people, was later disclosed to be Reading, Pa., a city that for 30 years was plagued and sometimes controlled by a criminal syndicate that paid off public officials to protect its gambling operations. Four years after that, Reading was again exposed to a national audience when an independent television company, Group W Corp., produced an hour-long documentary, “The Corrupt City.”

Fifteen years after the 1951 Kefauver hearings exposed Reading for what it was, the federal government was again in an anti-Mafia mode (download final report of the Kefauver Committee by clicking here (PDF document, 0.98 MB). The President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice formed a task force to prepare a report on the state of organized crime. Reading became a good source of information for commission investigators. In the previous 10 years, various agencies of the Justice Department had, at considerable cost, developed high-profile gambling, tax, and bootlegging cases in Reading that were successfully prosecuted in federal courts. Ironically, by the time Wincanton became a familiar name nationally, Berks County and Reading law enforcement officials had launched their own attack on local racketeering.

A pair of young University of Wisconsin political science professors arrived in Reading unannounced in May 1966. Dr. John A. Gardiner and David J. Olson said they had received a grant from New York City’s Russell Sage Foundation to write a book on small city politics. They said Reading was one of three or four cities whose political setup they would be analyzing. Actually, the President’s Commission was financing their study, fully aware of Reading’s history as a city where the rackets had flourished since Prohibition.

Using a list of 120 questions, commission survey crews interviewed hundreds of citizens, businessmen, politicians, professionals, and policemen. Gardiner and Olson pored through newspaper files and compiled a short history of illegal gambling, bootlegging, prostitution, and extortion in Reading. Their final report was entitled, “Wincanton: The Politics of Corruption.” Their findings were included in “Task Force Report: Organized Crime,” a document published in 1967 by the President’s Commission. It was the only section of the task force study dealing specifically with one city’s corruption problems.

Gardiner and Olson stated, “Although the facts and events of this report are true, every attempt has been made to hide the identity of actual people by the use of fictitious names, descriptions and dates.” They were about as successful in this subterfuge as was “Anonymous” in his 1997 novel “Primary Colors.” Only a Reading reader who didn’t recognize President Clinton’s character in that book might not have been able to identify Irv Stern as Abe Minker in the task force report.

More important than the rehash of the long reign of the racketeers, Gardiner and Olson probed deeply into the psyche of a community that put up with corruption for so long. The professors drew heavily on the findings of the Kefauver Committee, and from data compiled during the series of federal raids and trials during the McDevitt and Kubacki administrations.

Not at any time in the 20th Century, the investigators learned, had the Reading police force been allowed to completely run its own show. At one time, elected constables and policemen shared equal arresting powers. In 1907, the local Chamber of Commerce hired the New York Bureau of Municipal Research to look into the sad state of Reading’s police force. The bureau’s report of more than 100 pages was a broad indictment of mismanagement in law enforcement. It was also an early warning that was rarely heeded by the politicians for the next 10 years.

Instead of hiring the best applicants in those early years, it was solely a case of whom you knew. The politicians controlled all appointments. The New York experts found that in the previous 17 years, Reading police personnel had completely changed seven times. Rookies received on the job training, learning from “veterans” who knew their number was up after the next election. Men were being hired as cops at an age other cities would have forced them to retire. Since no physicals were required, many came aboard with chronic illnesses, but were paid full salary when out sick. Some could barely write their names, which didn’t really matter because few written records were kept. In police court cops told their version of the arrest, the magistrate passed judgment, and that was it. That future scourge, paperwork, had not yet infested Reading’s police department. The seven holding cells in the basement of City Hall were described as unsanitary “ancient torture dungeons.” City Hall at that time was on the northeast corner of South 5th and Franklin streets.

That old and forgotten study pointed out that the 94-man department was too small for a growing city approaching 100,000 population. It recommended hiring through civil service tests, including physical and mental examinations. Over the next 60 years, gradual improvements were made toward the goal of establishing a professional department, but one important change never happened—the police department remained at the mercy of each succeeding mayor.

“The Wincanton Report” illustrated this merry-go-round pattern in the case of Police Chief Robert Elliott. He had curbed outside racketeering as best he could during the pearly gray administration of James Bamford. When Dan McDevitt took office, he demoted Elliott because the chief said he would continue to go after organized crime wherever he found it.

One of the idiosyncrasies of Reading voters until 1984 was that they never reelected an incumbent mayor. A few mayors won second terms but never twice in a row. Because each new mayor invariably reshuffled the police brass, the department usually lacked stability and experienced officers who had administrative training. This weakened morale and played into the hands of the racketeers who were always ready with gifts for the disenchanted, underpaid patrolmen who had little respect for their superiors.

The activities of Abe Minker were thoroughly examined by the Wincanton authors. With sound federal government sources, they were able to assess records about Abe’s rise to power in 1945. By the time U.S. Sen. Estes Kefauver and his committee investigated the interstate activities of organized crime, Minker still shared power with other local racketeers. Abe and his brother, Isadore, were far less candid when they appeared before the committee than was Ralph Kreitz. But the questions they refused to answer by taking the 5th Amendment exposed not only their gambling operations, but also their reliance on the Philadelphia and New York mobs.

“Two basic principles were involved in Minker’s protection system,” the Wincanton Report stated. “Pay top personnel as much as necessary to keep them happy (and quiet) and pay something to as many others as possible to implicate them in the system to keep them from talking. The range of the system thus went from a weekly salary for some public officials to a Christmas turkey for patrolmen on the beat. Records from the numbers banks listed payments totaling $2,400 each week to locally elected officials, state legislators, the police chief, a captain in charge of detectives, and persons mysteriously labeled “county” and “state.” While lists of persons to be paid remained fairly constant, the amounts distributed varied according to fluctuating profitability of gambling operations at the time. Payoff figures dropped sharply when the FBI put the Cherry Street dice game out of business. When the game was running, one official was receiving $750 a week, the chief, $100, and a few captains, lieutenants, and detectives lesser amounts.”

The report pointed out that patrolmen learned the hard way to keep their mouths shut about reporting or making unassigned arrests for gambling or prostitution. Those who dared to buck the system ended up on the midnight shift. Despite these assumptions that numerous Reading elected officials were taking payoffs, one of a very few were ever charged with bribery.

When high school teachers complained about burlesque shows in the Park Theater, Jimmy Maurer was paying the mayor $25 a week to allow his nudies to perform, the report stated. Unnamed township officials were said to have paid a county official $5,000 to operate gambling tents for five nights each summer. State police were never called to close down that annual rural gambling event, the report claimed.

“Many other city and county officials must be termed guilty of nonfeasance,” the report continued, “although there is no evidence that they received payoffs, and although they could present reasonable excuses for their inaction.” Local judges did request an investigation by the state attorney general but refused to approve his suggestion that a grand jury be convened to continue the investigation. For each of these instances of inaction, a tenable excuse might be offered: the best patrolman should not be expected to endure harassment from his superior officers; state police gambling raids in a hostile city might jeopardize state-local cooperation on more serious crimes; and a grand jury probe might easily be turned into a whitewash by a corrupt district attorney.”

Charlie Wade was guilty of malfeasance when he paid $5,000 to Abe Minker to be appointed chief of police, the report stated. And Dan McDevitt was guilty of macing, a violation of his oath of office, by informing City Hall employees they were expected to contribute 2 percent of their salaries to the Democratic Party. By asking salesmen who sold equipment to the city to make voluntary contributions to the party, McDevitt and Kubacki were guilty of malfeasance, not just honest graft as Reading politicians came to regard such donations. And McDevitt’s revenge campaign of ticketing Reading Eagle Company delivery trucks was identified in the report as an act of misfeasance.

About the only positive finding in the study about Abe Minker: “He never, it might be added, permitted narcotics traffic in the city while he controlled it.” This could also be said about McDevitt and Kubacki. Detective John Feltman was given a direct order not to investigate gambling or prostitution, but also was given a free hand to undertake any investigation of illegal drugs he wanted to. During those two administrations very few drug arrests were made, but it wasn’t too many years later that the long war started and continues to this day.

When Kubacki became mayor in 1960 he maneuvered to gain control of the bureaus of building and plumbing inspection. The Wincanton Report explained why: “With this power to approve or deny building permits, Kubacki ‘sat on’ applications, waiting until the petitioner contributed $50 or $75, or threatened to sue to get his permit. Some building designs were not approved until a favored architect was retained as a consultant. At least three instances are known in which developers were forced to pay for zoning variances before apartment buildings or supermarkets could be erected. Businessmen who wanted to encourage rapid turnover of curb space in front of their stores were told to pay a police sergeant to erect “10-minute parking” signs. The report questioned whether this was honest graft.

Attempting to offer a fair and realistic big picture of Reading’s city government, Gardiner and Olson came to this conclusion:

“This cataloging of acts of nonfeasance, malfeasance, and misfeasance by Wincanton officials raises a danger of confusing variety with universality, of assuming that every employee of the city was either engaged in corrupt activities or was being paid to ignore the corruption of others. On the contrary, both official investigations and private research led to the conclusion that there is no reason whatsoever to question the honesty of the vast number of employees of the city of Wincanton. Certainly, no more than 10 of the 155 members of the Wincanton police force were on Irv Stern’s (Minker’s) payroll (although as many as half of them might have accepted petty Christmas presents (turkeys or liquor.) The only charge that can be justly leveled against the mass of employees is that they were unwilling to jeopardize their employment by publicly exposing what was going on.”

Some employees agreed to cooperate with federal investigators when they were convinced an honest attempt was being made to convict Minker and Kubacki. These few brave souls risked the mayor’s wrath by testifying before the grand jury in Philadelphia. Charlie Wade, at the risk of facing trial for perjury, really opened up, giving the government first-hand information on how the mob had thoroughly corrupted city officials during his time as chief.

Gambling became so imbedded in the social structure of Reading, the report pointed out, that reform movements seldom had a lasting effect on politics. In one year alone, it was estimated 272,000 persons paid to play bingo in the city. Fringe mobsters had an interest in the more profitable bingo establishments.

Most candidates for office grew up in neighborhoods where numbers were sold in most corner grocery stores. They or their parents belonged to social, political, athletic, or fire company clubs where slot machines and punchboards were as much a part of the milieu as jars of pickled eggs and sausage on the bar. However, it could be said that while a majority of the voters who felt no qualms about placing a bet with a bookie or playing the daily number, these same citizens would prefer honest politicians to those who weren’t. It was because of this hypocritical attitude, so prevalent all over the city, that victorious reform candidates never stayed in office long enough to change the system.

“While gambling and corruption are easy to judge in the abstract,” the report said, “they are never encountered in the abstract—they are encountered in the form of a slot machine which is helping to pay off your club’s mortgage, or a chance to fix your son’s speeding ticket, or an opportunity to hasten the completion of your new building by overlooking a few violations of the building code. In these forms the choices seem less clear.

“Furthermore, to obtain a final appraisal of what took place in Wincanton one must weigh the manifest functions served—providing income for the participants, recreation for the consumers of vice and gambling, etc.—against the latent functions, the unintended or unrecognized consequences of these events.”

Not only clubs relied on gambling for financial support. Business groups used lotteries to advertise “Downtown Reading Days.” Playground associations and churches sponsored lotteries, bingo and Las Vegas nights to pay for equipment in youth leagues. Union halls were hotbeds of all types of gambling. Far more than most cities of its size, Reading allowed itself to drift into a situation that left many, many of its organizations dependent upon gambling to survive. The direct consequence of this dependency was the election of officials who also relied heavily on gambling for financial support.

And the betting cancer spread even to our hallowed institutions, the report stated. It noted that “leading gamblers and racketeers were generous supporters of Reading charities.” Going back to Max Hassel and Dutch Mary, the city’s underworld folk heroes had promotional agendas, including spreading the wealth among the poor on holidays. Today it would be called marketing, akin to Nike’s giveaway programs in the sports community. Tony Moran won civic support by underwriting athletic teams. Abe Minker donated a $10,000 stained glass window to his synagogue and aided welfare groups and hospitals in Reading and other cities. Ralph Kreitz, with annual incomes of more than $100,000, gave much of his money to churches, hospitals and the underprivileged. Before his downfall, Ralph bought 7,000 Christmas trees for the poor, and chartered buses to take slum kids to Philadelphia baseball games.

This paradox of the Reading racketeer personality had deep roots. The public built an image of Max Hassel, Dutch Mary, and Tony Moran as honest-to-good-ness benefactors to the downtrodden. Minker never gained that status. The publicity about Minker’s dominance of the rackets brought to light by federal prosecutors and disgruntled gambling machine operators, finally soured voters on the sad condition of the city’s politics.

Business in general suffered because of the rackets. Cigar and candy storeowners who succumbed to the numbers rackets, were pinched financially during the occasional crackdowns on gambling by state or federal investigations. Because of the easy money, the storeowners had not established solid profit bases. The same could be said for contractors who relied on illicit deals with the city. Taking the crooked road usually left these outmoded businessmen behind in the technology race. They were often the uneducated and untrained who gained a certain social status by being in league with racketeers and politicians of their own ilk. Reputable businessmen who didn’t fall into the kickback trap profited in the long run.

A review of Reading’s political history offered researchers further understanding of why corruption was allowed to exist decade after decade. Things creaked along under many administrations that resisted innovation. During the ’20s and early ’30s when the population was growing, construction was booming with the advent of several new schools, the Lindbergh Viaduct, the Courthouse, the Abraham Lincoln Hotel, a new county prison, and several other major buildings. In 1925 the city and county discussed building a city hall/courthouse. But the city took the cheaper route by renovating the former boys high school building at 5th and Washington. Almost 80 years later, after alterations and an addition used by the police department, City Hall still serves the city.

The report was critical of the city’s commission form of government. It was not until 1996 that the voters finally caught up with the rest of the country by changing to the strong mayor-manager form.

In 1966, eight female pollsters from the Wisconsin Survey Research Laboratory randomly interviewed several hundred Reading residents. Using a lengthy questionnaire that took 45 to 75 minutes to complete, the pollsters tried to get people to answer all the queries. In a nutshell this is what the pollsters found out:

“The people of Wincanton apparently want both easily accessible gambling and freedom from racket domination.”

The professors heading the study had other opinions:

“On balance, it seems far more likely to conclude that gambling and corruption will soon return to Wincanton (although possibly in less blatant forms) for two reasons—first, a significant number of people want to be able to gamble or make improper deals with the city government. (This assumes, of course, that racketeers will be available to provide gambling if a complacent city administration permits it.) Second, and numerically far more important, most voters think that the problem has been permanently solved, and thus they will not be choosing candidates based on these issues in future elections.”

Five years after The Wincanton Report was published, Reading was reminded once again of its recent past when “The Corrupt City” was being shown on national television. As viewers were told, racketeering was not as visible in 1971, but the threat of its revival seemed possible.

This documentary was a spinoff of Wincanton, but it was graphic evidence of why the city had gained its terrible reputation one decade earlier. The film introduced a shadowy figure, identified only as a convicted murderer who had killed a former racketeer leader. It was Johnny Wittig telling how he transferred Abe Minker’s payoff money to Police Chief Charlie Wade on a lonely country road. Then there was Wade in his automobile telling the interviewer how his tape recorder picked up conversations with passengers at that same money exchange site in the country. Also, Charlie and his German shepherds were seen at his fenced-in Cumru Township home where he feared the mob would come after him because of his incriminating testimony in court.

Conversations with political club members were taped, documenting that many citizens still wanted illegal gambling although they didn’t like political shakedowns.

Tom McBride, the Pennsylvania attorney general, had this to say about the political picture and the role Abe Minker played:

“Reading seemed to me to always be in a vacuum, a vacuum of leadership, a vacuum of people who cared deeply enough about the city, and a single man driven by single-minded objectives moved in to fill that vacuum. The usual business leadership and political focus seemed to evaporate and he took over. And once the pattern was set, he held control, almost in a feudal sense.”

Victor Yarnell, mayor at the time of filming, and his police chief, Bernie Dobinsky, were quite open about the threat of racketeers making a comeback in the near future. Dobinsky frankly stated it was a strong possibility that could happen. He told about a mobster offering him weekly sums to allow a gambling joint to operate. He rejected the offer, but said the realization was that “this guy was ready to pay to stay in business. I don’t think it would take too long because I really think there are people poised just waiting for this department to relax. From information given to me and my personal contacts, I don’t doubt that there would be a racket element ready to move in.”

The film’s narrator, Rod MacLeish, asked Yarnell about this rackets group Dobinsky was talking about and recent offers made to people in his administration.

“Well, it occurred very soon after I took over this job,” Yarnell stated. “He visited me and said he would be an ideal man to have as a go-between with the police and the racketeers he knew very well. He did this with a straight face and I thought he really felt this was a good idea. But I didn’t think too much about it and I tended to laugh it off, and that was all we heard about it.”

Paul Galan, director of the Group W Urban American film, recalled that City Hall personnel were not overly cooperative when his TV interviewers arrived in town. But the production crew overcame this reluctance and succeeded in talking to enough people to gain an overview of how things operated during the corrupt years. He said at the 2006 film festival that he was amazed by the Runyonesque characters his crew met in Reading.

“Charlie Wade was one of a kind,” Galan said. “He was fascinating in that he really seemed driven to have a good police force but wanted the prestige even more. He was a complex individual.”

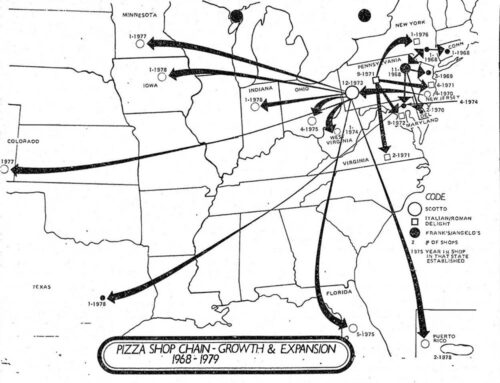

Although racketeering in Reading declined during the late 1960s, it did not disappear. Numbers writing continued even after 1978 when the Pennsylvania State Lottery was introduced. With the loss of many industrial jobs, the later purveyors of sports betting and numbers sharply decreased. Former factories gave each numbers bank a strong base in which to operate. But it remained a profitable business for a greatly reduced number of independents.

When the state legalized off track betting, Berks County was awarded the first OTB parlor.

The arrest of a numbers writer or bookie has been a rare event in recent years as police spend much of their time and resources waging war on drug gangs. Put in prospective, the present battle seems to belittle the long fight against vice back in the mid-20th Century. The violence and overall social problems resulting from today’s sale of illegal drugs and its resultant violence is certainly of far greater concern than was the gambling and prostitution of that distant era. But the political base of today’s society is certainly an improvement over city government then. As predicted by many, gambling became legal.