After Reading was sketched out by Thomas Penn in 1748, most of the development centered around Market Square (present day Penn Street) and west in almost a straight line to the Schuylkill River.

For the next 100 years, development stayed mostly in that area and only began to break out to the southwest in the decades before the Civil War.

The southwest area of the city was the logical direction for development for a variety of factors.

The land was flat and accessible to the downtown. Bingaman Street was the main road to Lancaster, and it was the original southern boundary of Penn’s town.

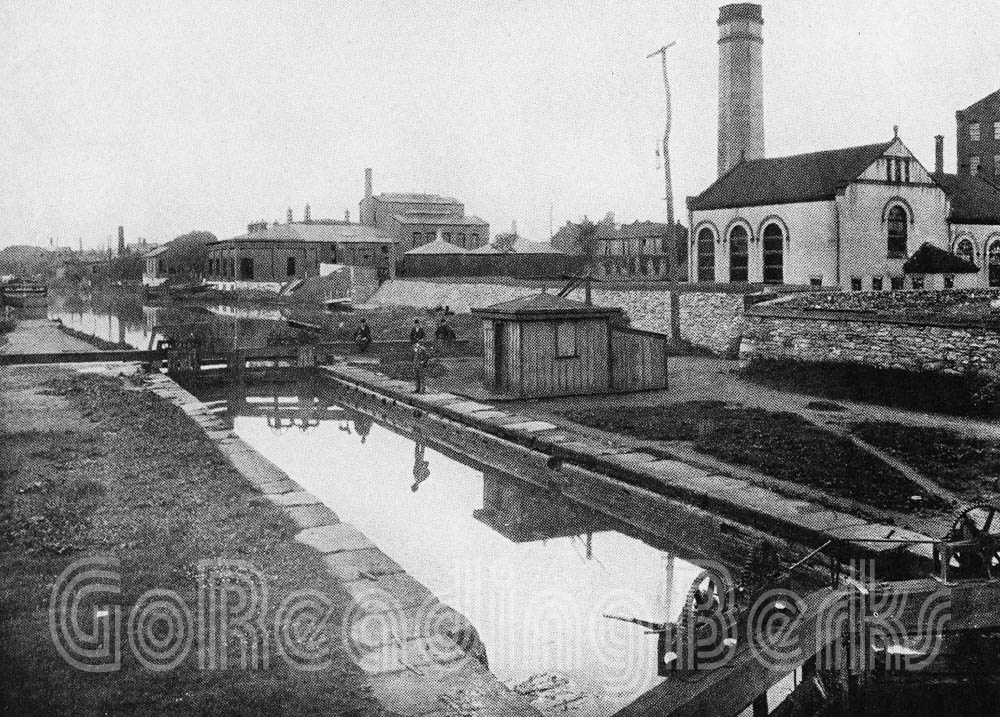

In 1825, the Schuylkill Canal on the east bank of the river, was opened to Philadelphia, and the Union Canal, between Reading and Middletown, was opened in 1828. The focal point of the two systems was in southwest Reading.

Below: Schuylkill Canal (Navigation). Foot of 6th Street.

A decade later, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad was opened to Pottstown, and by 1841, the line ran from Philadelphia to Pottsville.

The railroad was a clever piece of engineering. It was laid out on grades designed to use the least amount of energy to haul anthracite to Philadelphia, and to haul the empty coal trains back to Pottsville.

The P&R engineers, who wanted to avoid both competing for space with the canals and the frequent flooding of the river, laid the main line along Seventh Street, then in the eastern outskirts of the town.

The upshot was that southwest Reading was situated between the rails and the canals, and was primed for heavy development.

The first railroad shops were built at 7th & Chestnut Streets. Over the next few decades, a huge complex of shops developed.

What is left of that early complex are the buildings which are now used by the Reading Foundry and Supply Co.

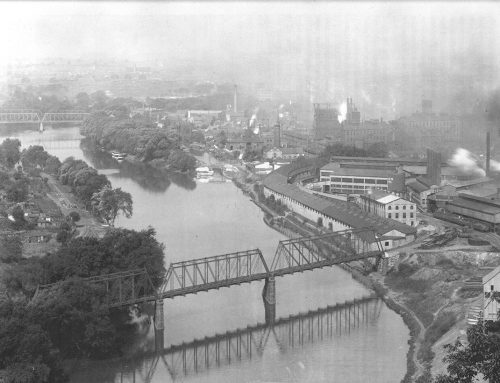

There was other development attracted by the transportation possibilities. The Reading Iron and Nail Works, the city’s first heavy industry, was established in 1836 on the canal at the foot of Seventh Street.

The factory produced the city’s first machine-made nails, and later became the Reading Iron Co.

Below: View from about 1900 of the Schuylkill River looking toward Reading from the hill at the foot of South 9th St.. The extensive Reading Iron Works was located in South Reading along the banks of the Schuylkill River.

In 1851, William Harbster opened a blacksmith shop on Canal Street near Fifth, a business which rapidly grew into the Reading Hardware Co. The firm employed 1,500 workers who made made locks and bolts and other fixtures good enough to win first prizes in both the Centennial and Paris expositions in the latter part of the century.

Early in the 1850s, the Wyomissing Wool Manufacturing Co. built a large plant on South Fifth Street between Laurel and Willow, and in 1871, the Hendel brothers, hat makers who got their start in Adamstown, took over the plant.

By 1876, it was considered the largest hat factory in the country.

This industrial prosperity along the railroad and the canal greatly affected the development of the rest of southwest Reading.

In 1877, Charles Raymond Heizmann founded the Penn Hardware Company. Penn Hardware made some of the finest brass and steel hardware produced in America.

Below: Penn Hardware Company Complex, 1922.

While the elegant town houses of the Penn Square area began to appear on Sixth Street, Fifth Street and portions of Franklin Street, most of the area was developed by row upon row of more modest late-Federal style homes.

These homes were often frame, mostly designed as residences for the blue-collar workers of the area’s industries, and the area became one of the most densely populated in the city.

These industrial workers came largely from waves of European immigration, and successive waves of Irish railroad workers, and Polish and Italian industrial workers, moved through the neighborhoods, with one wave achieving affluence and moving on, to be replaced by another wave.

These early immigrants were generally tolerated, but with some contempt, by more established citizens.

In the 1860s, the Irish fondness for strong drink became at least a matter of widespread belief, if not of actual practice, through thorough, and sometimes embellished, reporting of such incidents in the local newspapers.

In 1896, an enterprising reporter tried to get some insight into the Italian community, where little English was spoken, by talking to a grocer at Sixth and Willow streets who had taught himself Italian.

“They are a jolly class of people when you learn to know them,” the grocer said, and the rest of the article was a long recitation on the making of macaroni – and the grating of cheese and the making of sauce.

In 1899, a news account dutifully reported the arrest of 13 guests at a Polish wedding party on Minor Street, including the groom, following a brawl.

The area also boasted the city’s first Jewish synagogue,”Oheb Sholom, formed in 1864 in rented rooms at Sixth and Franklin streets, where it stayed for many years.

Though the synagogue was there, there was no great concentration of Jews in that area or anywhere else.

In 1871, the South Reading Market House opened at Sixth and Bingaman streets, capping a long civic drive to rid Penn Square of its market sheds – described as a “burning disgrace” by one editorial writer who also lamented Reading’s reputation as “a small Dutch village . . . somewhat noted for the manufacture of wool hats.”

The new market house was grand and opulent by comparison, with the stands indoors and lit by gas lamps. In 1874, the old cast-iron supports of the miserable market sheds were used to support a portico constructed around the new market house.

Below: South Reading Market House.

Farmers in outlying areas often had to leave home at 9 p.m. to haul their goods to Reading, since the first shoppers would show up as early as 4 a.m., and most shoppers, their baskets filled, were gone by 7 a.m.

In the summer of 1897, cucumbers were three for a nickel, whole watermelons were 30 to 40 cents, and tomatoes were 10 cents a box.

Spring chickens live, were 20 to 30 cents a pound.

Dressed, they cost twice as much. Old chickens, in plentiful supply, were 14 cents a pound. Butter was 20 cents a pound, and eggs, 18 cents a dozen.

That era has passed. The big industrial plants are gone, victims of floods or fires, or converted to other uses. Many of the early working-class houses fell to floods and urban renewal efforts.