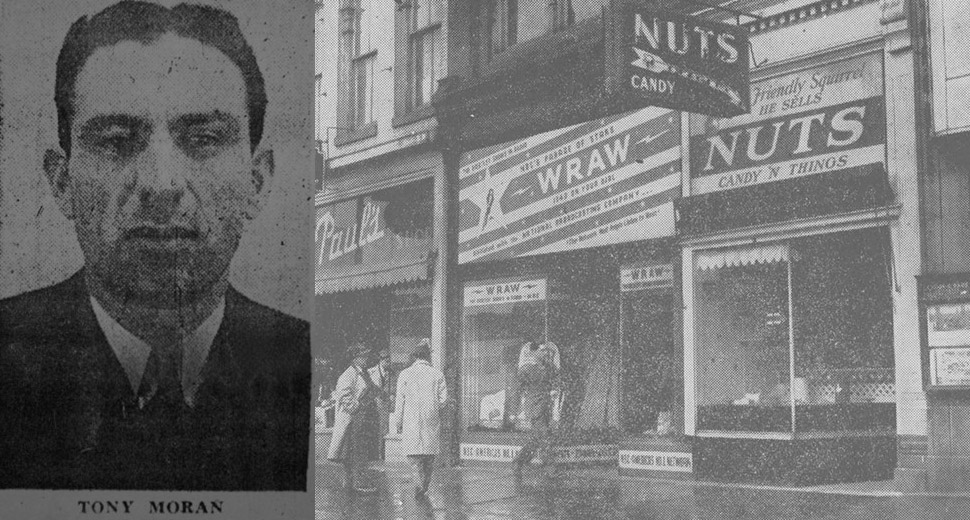

From Anthony Mirenna to Tony Moran: The Making of a Racketeer

Born Anthony Mirenna in 1903 in Tunis, Africa, Tony Moran immigrated to the United States with his family and eventually settled in Reading, Pennsylvania. By the 1930s he was a naturalized citizen. Unlike the flamboyant bootleggers and gangsters of Prohibition who craved headlines, Moran operated with quiet precision. His arrest record was remarkably slim compared to his contemporaries, yet he built one of the most sophisticated rackets in Reading’s history.

The pivotal moment in his rise came in 1933 with the assassination of Max Hassel, Reading’s famed “beer baron.” Hassel’s funeral drew an estimated 10,000 mourners and left a void in the city’s criminal hierarchy. While other racketeers fought openly for power, Tony Moran methodically positioned himself to inherit Hassel’s mantle. Through patience, cunning, and an almost supernatural ability to avoid law enforcement attention, he became Reading’s undisputed king of vice.

The Architecture of a Criminal Empire

The Numbers Game

By the mid-1930s, Tony had established himself as the operator of “a couple of large numbers banks,” as federal investigators would later describe his operations. The numbers game, which had originated in 18th-century England as the “policy game,” proved to be the most profitable racket ever devised. Players would bet on three-digit numbers drawn from various sources—initially from England’s government bond drawings, later from stock market figures or race track results.

Tony understood the numbers game’s appeal to Reading’s working-class population better than perhaps any other racketeer of his era. For as little as a penny, factory workers could dream of hitting the number that paid 600-to-1 odds. The mathematical reality was harsh—the true odds were 1,000-to-1—but the psychological appeal was irresistible. Tony’s operations served not just as gambling enterprises but as informal banking systems for communities often excluded from traditional financial institutions.

His numbers banks employed dozens of writers who collected bets at factories, barbershops, corner stores, and social clubs throughout Reading. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad shops, the city’s hosiery mills, and the various foundries all had their regular numbers writers, many of whom reported directly to Tony’s organization. The operation was so pervasive that it functioned almost like a parallel economy, with its own credit systems, collection methods, and dispute resolution procedures.

Real Estate Portfolio: The Legitimate Face of Ill-Gotten Gains

Tony’s criminal success translated into substantial legitimate investments. By the time of his death in 1945, he owned fifteen properties throughout Berks County, a portfolio worth several hundred thousand dollars in 1940s currency—equivalent to millions today. These holdings served multiple purposes: they provided a means to launder criminal proceeds, established Tony as a respectable businessman in certain circles, and created legitimate income streams that could be reported to tax authorities.

The crown jewel of Tony’s real estate empire was 608 Cherry Street, which housed one of the most profitable brothels in Reading’s red-light district. Managed by the notorious Dutch Mary Gruber, this establishment became legendary during World War II when soldiers from nearby Indiantown Gap Military Reservation flooded into Reading on weekend passes. The intersection of 6th and Cherry Streets became so congested with military personnel that local authorities had to implement special traffic control measures.

The Underground Kingdom: 529 Penn Street

Tony’s most sophisticated operation centered on the subterranean gambling complex beneath Cole Watson’s basement poolroom at 529 Penn Street. This underground network represented the pinnacle of 1940s illegal gambling technology and organization. The main room could accommodate dozens of players at multiple card tables, while smaller adjacent rooms served specialized functions—private high-stakes games, a counting room for the night’s receipts, storage for gambling equipment, and even a small kitchen where food was prepared for all-night gaming sessions.

The complex featured multiple entrances and exits, including a tunnel system that connected to other basement establishments along Penn Street. This network allowed players and operators to move undetected between venues and provided multiple escape routes during the rare police raids. The ventilation system was sophisticated enough to handle cigar and cigarette smoke from dozens of patrons, while soundproofing prevented the noise of gambling from reaching street level.

Tony’s gaming operation attracted players from across southeastern Pennsylvania and beyond. High-stakes poker games regularly featured pots of several thousand dollars—enormous sums for the 1940s. The establishment maintained its own credit system, with trusted players able to sign markers that were honored throughout Reading’s gambling community. Professional dealers, many trained in the gaming houses of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Saratoga Springs, New York, ensured that games ran smoothly and professionally.

The Prostitution Network: Reading’s Red-Light Infrastructure

While numbers running provided Tony’s financial foundation and gambling offered his most prestigious operations, prostitution completed his vice trifecta. Tony’s approach to managing prostitution was characteristically systematic and businesslike. Rather than operating as a traditional pimp, he functioned more like a criminal executive, overseeing a network of establishments and ensuring smooth operations through political protection and law enforcement cooperation.

The 608 Cherry Street establishment, managed by Dutch Mary Gruber, was just one piece of a larger network. Tony maintained interests in multiple houses throughout the city’s tenderloin district, which stretched from the railroad tracks near Franklin Street down to the industrial areas near the Schuylkill River. Each establishment served different clienteles: some catered to factory workers seeking quick encounters during lunch breaks, others provided more upscale services for visiting businessmen and local professionals.

During World War II, Tony’s prostitution network experienced unprecedented prosperity. Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, located just outside Reading, housed thousands of soldiers in various stages of training and deployment. On weekends, these men descended on Reading with military pay burning holes in their pockets and limited time to spend it. The economic impact was so significant that local businesses, both legitimate and illegal, restructured their operations to accommodate the military influx.

Dutch Mary Gruber herself became something of a folk legend during this period. A savvy businesswoman who understood both the desires of her clientele and the necessities of political protection, she operated with such efficiency that her establishment rarely faced serious legal challenges. When arrests did occur, they were typically resolved through modest fines paid to cooperative aldermen, allowing operations to resume with minimal interruption.

The Web of Political Protection

Tony Moran’s criminal empire could not have functioned without extensive political protection, a fact that distinguished Reading from many other cities where organized crime operated. The relationship between racketeers and politicians in Reading was characterized by mutual benefit rather than simple corruption. Politicians needed the financial support and vote-getting capabilities that organized crime could provide, while racketeers required the legal immunity that political protection offered.

The Police Partnership

Tony’s relationship with the Reading Police Department exemplified the sophisticated corruption that characterized the city during his era. Rather than simply bribing individual officers, Tony’s organization worked to establish systematic protection that operated at departmental levels. This arrangement ensured that raids, when they occurred, were largely theatrical events designed to satisfy public pressure while causing minimal disruption to actual operations.

The police partnership manifested in several ways. First, Tony’s organization received advance warning of any genuine law enforcement interest in their operations. This intelligence network allowed gambling games to be temporarily suspended, prostitution houses to reduce their visibility, and numbers writers to avoid their usual locations when necessary. Second, when arrests did occur, they typically involved low-level employees who could be quickly bailed out and whose fines were covered by the organization.

Most importantly, the police partnership provided Tony’s operations with what amounted to security services. Officers would patrol areas around major gambling venues, ostensibly for law enforcement purposes but actually to warn of any unusual activity or potential threats from competing criminal organizations. This protection was particularly valuable during high-stakes gambling events that attracted players carrying large amounts of cash.

City Hall Connections

Tony’s political connections extended beyond the police department to include relationships with key figures in Reading’s city government. While the specific details of these relationships were carefully guarded secrets, their existence became evident through the pattern of city services and regulatory decisions that consistently favored Tony’s interests.

Building inspectors rarely found violations in properties associated with Tony’s organization, despite the obvious structural modifications required to create underground gambling facilities. Liquor license applications connected to Tony’s network moved through the approval process with unusual speed and success rates. City contracts for construction and services frequently went to companies that maintained relationships with Tony’s organization, creating a web of economic interdependence that strengthened his political protection.

The sophistication of these arrangements reflected Tony’s understanding that sustainable criminal operations required integration with legitimate power structures. Rather than operating as an outlaw organization in conflict with established authority, Tony’s empire functioned as a parallel government that provided services the official system couldn’t or wouldn’t offer while maintaining cooperative relationships with legitimate authorities.

The Wartime Boom: 1941-1945

World War II transformed Tony Moran from a successful local racketeer into the undisputed king of Reading’s vice industry. The establishment of Indiantown Gap Military Reservation as a major training facility brought thousands of soldiers into the area, each representing a potential customer for Tony’s various enterprises. The economic impact of this military presence cannot be overstated—it represented the most significant influx of disposable income and demand for entertainment services in Reading’s history.

Military Clientele and Economic Expansion

Soldiers arriving at Indiantown Gap came from across the United States, many experiencing urban nightlife for the first time. They carried military pay that, while modest by today’s standards, represented significant spending power in 1940s Reading. More importantly, these men faced the psychological pressures of impending deployment to combat zones, creating an atmosphere where normal social inhibitions were relaxed and immediate gratification became paramount.

Tony’s organization responded to this opportunity with characteristic efficiency. The gambling operations expanded to accommodate larger crowds and longer gaming sessions. Card games that had previously operated only on weekends now ran continuously from Friday evening through Sunday night. New games were introduced to appeal to military personnel familiar with different regional gambling traditions.

The prostitution network underwent similar expansion. New establishments opened in strategic locations between Indiantown Gap and downtown Reading. Existing houses extended their hours and increased their staffing. A sophisticated transportation system developed, with taxi drivers and other local entrepreneurs providing discrete transportation services between the military reservation and the city’s entertainment district.

Perhaps most significantly, Tony’s organization developed new services specifically designed for military clientele. Credit systems were established that allowed soldiers to gamble or obtain services immediately upon arrival in Reading, with payment deducted from their military pay through cooperative arrangements with local businesses. Special rates and packages were developed for groups of soldiers celebrating birthdays, promotions, or imminent deployment.

The Cherry Street Phenomenon

The intersection of 6th and Cherry Streets became legendary during the war years, with 608 Cherry Street serving as the epicenter of military entertainment in Reading. On typical weekend evenings, the area resembled a military parade ground more than a residential neighborhood. Soldiers in various uniforms—Army, Navy, Marines, and Army Air Corps—lined the streets waiting for their turn at Dutch Mary’s establishment.

The scene became so prominent that it attracted attention from military authorities, local religious groups, and eventually federal investigators. Military police began conducting regular patrols in the area, ostensibly to maintain order but often simply to ensure that soldiers didn’t become too disruptive. Local residents complained about noise, public intoxication, and the obvious nature of the commercial activities, but their protests carried little weight against the economic benefits the military presence brought to the broader community.

Dutch Mary Gruber herself became something of a local celebrity during this period. Newspaper society columns, while never explicitly mentioning her profession, occasionally included references to her attendance at local events and her contributions to various charitable causes. She was known to maintain cordial relationships with several prominent local businessmen and even some clergy members, reflecting the complex social dynamics that characterized Reading during the war years.

Organizational Adaptations

The massive increase in business during the war years required significant organizational changes within Tony’s criminal empire. New personnel were recruited and trained to handle increased volume across all operations. Security measures were enhanced to protect against both law enforcement attention and potential competition from other criminal organizations seeking to capitalize on the military bonanza.

A sophisticated logistics system developed to manage the flow of customers, money, and services. Coordination between different operations became crucial—soldiers might spend an evening gambling, visit a brothel, and place numbers bets before returning to Indiantown Gap, requiring seamless transitions between different segments of Tony’s organization.

The financial success of the war years also presented new challenges. The sheer volume of cash generated by Tony’s operations required careful management to avoid attracting unwanted attention from federal tax authorities. Money laundering through legitimate businesses became more sophisticated, with investments in real estate, local businesses, and even war bonds serving to legitimize criminal proceeds.

The Shooting – March 21, 1945

In the early morning hours of Wednesday, March 21, 1945, Tony Moran’s career and life ended violently. At 12:40 a.m., gunfire erupted inside a storeroom gambling den hidden behind a cigar shop at 529 Penn Street. The wartime curfew had closed theaters and bars at midnight, but the dice and card games inside continued.

As about 25 patrons scrambled to flee, four bullets struck Moran in the chest and side. Still conscious, he collapsed to the floor. Harold “Tiny” Hoffner carried him outside, placed him in a car, and rushed him to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he died about an hour and a half later.

A police sergeant tried to question him before death. Moran, groaning, muttered only:

“Let me alone. Put me to sleep. No one did it.”

Below: Two men gaze curiously into the storeroom at 529 Penn St. while a third passes the doorway of the place which was used as a gambling establishment, in which Tony Moran, gambler and reputed top man of Reading’s underworld, was fatally shot. Signs and photos of radio entertainers fill the display windows, with a shoe shine stand and cigar counter occupying the front of the storeroom. The shooting occurred at 12:40 a.m. on Wednesday, March 21.

The Scene of the Crime

The gambling den where Tony met his end was a testament to his organizational skills and attention to detail. The main room, carved out of the basement space beneath Penn Street, could accommodate several dozen players at multiple tables. Professional-grade poker tables, imported from gaming supply companies that served legal establishments in Nevada and illegal ones everywhere else, provided the infrastructure for serious gambling.

The atmosphere on the night of Tony’s murder was typical for a weeknight gaming session. Regular players had gathered for what appeared to be routine card games, though some participants later suggested that unusually large amounts of money were in play that evening. The presence of approximately twenty witnesses to the shooting indicates that the gambling operation was in full swing when Johnny Wittig arrived.

The room’s layout would prove crucial to the enduring mystery surrounding Tony’s death. Multiple card tables meant that not all witnesses had clear sight lines to every part of the room. The basement location, with its low ceilings and numerous support pillars, created shadows and blind spots that could conceal a shooter’s identity. Most significantly, a railing separated the main gaming area from an elevated section where spectators could observe the action without participating directly.

The Shooting

Johnny Wittig’s arrival at the gambling den was not unusual—he was known to frequent Tony’s establishments and had gambling debts of his own. What transformed a routine evening into a murder scene was Wittig’s decision to draw a .38 caliber revolver and fire multiple shots at Tony Moran. The shots were fatal, but the exact circumstances of the shooting remain disputed to this day.

Of the approximately twenty people present during the shooting, none provided testimony that they actually witnessed Johnny Wittig pull the trigger. This extraordinary fact would fuel conspiracy theories for decades. Witnesses heard gunshots, saw Tony Moran fall mortally wounded, and observed Johnny Wittig with a gun, but the crucial moment of the actual shooting apparently occurred without clear observation by any of the numerous people in the room.

The absence of eyewitness testimony to the actual shooting was compounded by the fact that no murder weapon was ever recovered. While .38 caliber bullets killed Tony, and Johnny was known to own a .38 Colt revolver, the specific gun used in the murder was never found despite extensive searches of the crime scene and Johnny’s known haunts.

The Investigation and Trial

The Reading Police Department’s investigation of Tony Moran’s murder was, by contemporary standards, relatively thorough. Detectives interviewed dozens of witnesses, searched the crime scene extensively, and built what they considered a solid case against Johnny Wittig. The investigation was complicated, however, by the obvious reluctance of many witnesses to provide detailed testimony about events at an illegal gambling establishment.

Johnny Wittig was arrested, charged with first-degree murder, and brought to trial in Berks County Court. The prosecution’s case relied heavily on circumstantial evidence: Johnny’s presence at the scene, his known conflicts with Tony Moran, and witness testimony that he was observed with a gun immediately after the shooting. The defense argued that the evidence was insufficient to prove Johnny’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, particularly given the absence of eyewitness testimony to the actual shooting.

The jury ultimately found Johnny Wittig guilty of third-degree murder, a verdict that reflected their belief that he was responsible for Tony’s death but that the killing lacked the premeditation required for first-degree murder. Judge sentenced Johnny to 10 to 20 years in state prison, a substantial term but one that left open the possibility of parole after serving the minimum sentence.

Below: Johnny Wittig climbs the steps from the cell block to police headquarters on the first floor of city hall while on his way to the district attorney’s office for questioning in the slaying of his former pal, Tony Moran. Later he was formally charged with murder. Wittig gave himself up six hours after Moran was fatally wounded in a storeroom crap joint at 529 Penn St.

Below: Constable Paul Weidner, in shirtsleeves, serves as a model while Dr. George P. Desjardins (wearing coat, standing) shows the course taken by the bullets fired into Tony Moran in a Penn Street gambling place on the morning of March 21. The physician was called upon to give the demonstration during the hearing of a murder charge against John Wittig in the office of Alderman C. Leroy Wanner. On the bench, left to right, are Arthur Featherman, Lieut. Harry Bowman and Wittig. Man with back to camera is Mark C. McQuillen, defense attorney.

The Conspiracy Theory: An Alternative Narrative

Even before Johnny Wittig’s trial concluded, whispered alternative theories about Tony Moran’s murder began circulating through Reading’s criminal underworld. The most persistent and detailed of these theories suggested that Johnny was not the actual shooter but rather a paid fall guy who agreed to take responsibility for the murder in exchange for financial compensation and future employment opportunities.

According to this conspiracy narrative, Abe Minker orchestrated Tony’s elimination as part of a calculated plan to consolidate control over Reading’s rackets. Tony Moran represented the last significant obstacle to Abe’s ambition to become the city’s undisputed crime boss. Rather than engage in a potentially destructive gang war, Abe allegedly chose to eliminate Tony through a carefully planned assassination that would remove his rival while providing a scapegoat who could be trusted to remain silent.

The conspiracy theory identified Harold “Tiny” Hoffner, a close associate of Tony Moran’s, as the actual shooter. According to this version of events, Tiny positioned himself behind the railing in the elevated section of the gambling den, providing him with a clear shot at Tony while remaining partially concealed from most witnesses. When the shooting occurred, Johnny Wittig was positioned to appear responsible while the real gunman remained undetected.

Several factors lent credence to this conspiracy theory. First, Johnny Wittig’s behavior after his release from prison seemed to support the idea that he had been compensated for taking the blame. Rather than seeking revenge against those who had betrayed him or attempting to rebuild his own criminal organization, Johnny went to work directly for Abe Minker, eventually becoming his most trusted enforcer. This career trajectory seemed inconsistent with someone who had been wrongly imprisoned for another man’s crime.

Second, the financial resources available to Johnny after his release suggested compensation beyond what he could have accumulated through legitimate employment during his brief periods of freedom before the murder. Johnny’s ability to maintain a comfortable lifestyle and his apparent lack of concern about his financial future indicated access to resources that the conspiracy theorists attributed to payments from Abe Minker.

Third, the timing of Tony Moran’s murder coincided perfectly with Abe Minker’s rise to power in Reading’s criminal hierarchy. Within months of Tony’s death, Abe began consolidating control over the various rackets that Tony had managed, suggesting advance planning rather than opportunistic expansion into a power vacuum.

The Question of Motive

Understanding Johnny Wittig’s motive for killing Tony Moran requires examining the complex relationship between the two men and the broader dynamics of Reading’s criminal community in the mid-1940s. The most commonly cited motive involved a financial dispute dating back to 1939 when both men were convicted of running a fraudulent charitable lottery for the Elks Crippled Children Benefit.

Both Tony Moran and Johnny Wittig received nine-month sentences and 1,000 fines for their roles in the phony charity scheme. Tony, with his superior financial resources, quickly paid his fine and secured his release after serving the minimum sentence. Johnny, however, could not raise the1,000 fine and was forced to serve additional time in Berks County Prison to work off the debt. This experience allegedly created lasting resentment against Tony, who Johnny felt had abandoned him when he could have easily covered the fine.

The charitable lottery incident revealed important dynamics in the relationship between Tony and Johnny. While both men were involved in the scheme, Tony clearly held the senior position and controlled the financial resources generated by the operation. Johnny’s inability to pay his own fine demonstrated his subordinate status within Tony’s organization and highlighted the economic disparities between different levels of the criminal hierarchy.

However, the conspiracy theory proposed a much more complex motive involving Johnny’s alleged secret arrangement with Abe Minker. According to this narrative, Johnny’s resentment against Tony made him an ideal candidate for Abe’s assassination plot. Rather than acting out of pure personal animosity, Johnny supposedly agreed to kill Tony as part of a business arrangement that would provide him with financial compensation and guaranteed employment in Abe’s expanding organization.

The Funeral

On March 30, 1945, Reading witnessed one of its most extraordinary funerals. Thousands lined Penn Street as more than 6,000 mourners filed past Moran’s bier at 1011 Penn Street.

He lay in a $2,000 bronze coffin, surrounded by 65 floral tributes. Eleven funeral cars and twenty private vehicles formed the cortege to Charles Evans Cemetery. Police directed traffic for the throngs who came to glimpse the underworld czar one last time.

Below: An estimated 6,000 people filed past the body of Tony Moran, the slain gambler and reputed underworld leader, as it lay in state at his home, 1011 Penn Street. The following day, Moran was buried in Charles Evans Cemetery, resting in a $2,000 bronze coffin.

Aftermath: Abe Minker’s Rise

Moran’s death left a power vacuum. His rackets splintered briefly, but within months Abe “the General” Minker consolidated control, especially through his Fairmore Amusement Company slot machine empire. By the 1950s, Minker dominated Reading’s underworld until federal scrutiny—particularly the Kefauver Committee hearings—exposed his operations.

Legacy and Historical Impact

Tony Moran’s influence on Reading’s criminal history extends far beyond his twelve-year reign as the city’s vice king. His organizational innovations, business practices, and approach to managing relationships with legitimate authorities established patterns that would characterize organized crime in Reading for decades after his death.

Organizational Innovations

Tony’s most significant contribution to organized crime methodology was his development of integrated operations that combined multiple forms of illegal activity under centralized management. Rather than specializing in a single racket, Tony created a criminal conglomerate that offered gambling, prostitution, and lottery services to overlapping customer bases, maximizing revenue while minimizing operational costs.

This integrated approach required sophisticated coordination between different segments of the organization. Numbers writers needed to be aware of gambling events that might attract their customers. Prostitution establishments had to coordinate with gambling venues to provide comprehensive entertainment packages. Slot machine operators required intelligence about law enforcement activities that might affect other parts of the organization.

Tony’s organizational model also pioneered the use of legitimate businesses as fronts for criminal operations. His real estate investments provided not only money laundering opportunities but also physical infrastructure for illegal activities. Properties could be purchased, modified for criminal use, and operated with the appearance of legitimate business purposes, providing both operational security and legal protection.

Political Integration Model

Perhaps even more important than Tony’s organizational innovations was his development of a sophisticated model for integrating criminal operations with legitimate political structures. Rather than operating in opposition to established authority, Tony’s organization functioned as a parallel government that provided services the official system couldn’t offer while maintaining cooperative relationships with legitimate authorities.

This integration model required understanding both the needs of political figures and the capabilities of criminal organizations. Politicians needed financial support for campaigns, vote-getting assistance in key constituencies, and occasionally personal services that couldn’t be obtained through legitimate channels. Criminal organizations needed legal protection, advance warning of law enforcement activities, and favorable treatment in regulatory matters.

The success of Tony’s political integration model is evident in the minimal law enforcement interference his operations faced throughout his twelve-year reign. Major raids were rare and typically resulted in minor penalties that were quickly absorbed as business costs. More importantly, Tony’s organization received the kind of unofficial cooperation from police and city officials that allowed complex operations like the Penn Street gambling complex to function openly for years without serious interference.

The Shadow of Violence

Despite Tony’s generally peaceful approach to criminal enterprise, his violent death served as a reminder that organized crime ultimately rests on the foundation of potential violence. The circumstances of his murder—occurring at the height of his power, in the heart of his own territory, surrounded by his own people—demonstrated the inherent instability of criminal leadership positions.

Tony’s murder also established a precedent for violent succession in Reading’s criminal hierarchy. The conspiracy theories surrounding his death suggested that violence was not merely a tool for resolving disputes but a strategic weapon for ambitious rivals seeking to advance their positions. This precedent would influence criminal politics in Reading for decades, as potential successors understood that achieving and maintaining power might require both the threat and application of deadly force.

Cultural Impact

Tony Moran’s story became part of Reading’s cultural mythology, representing both the excitement and danger of the city’s criminal heritage. Stories about the underground gambling complex, the wartime prosperity of the Cherry Street district, and the mysterious circumstances of his murder were passed down through generations of Reading residents, becoming part of the city’s informal historical narrative.

The romanticization of Tony’s era reflected a complex mixture of nostalgia and moral ambiguity that characterized public attitudes toward organized crime in mid-20th century America. Tony was remembered not as a dangerous criminal but as a successful businessman who operated outside conventional legal boundaries, providing services that people wanted but couldn’t obtain legally.

This cultural legacy influenced how subsequent generations of Reading residents viewed organized crime and its relationship to legitimate society. Tony’s example suggested that criminal organizations could function as integral parts of the community rather than external threats to social order, a perspective that would complicate law enforcement efforts and public policy discussions for decades.

Conclusion: The Man Behind the Legend

Tony Moran’s story embodies the contradictions and complexities of organized crime in mid-20th century America. He was simultaneously a successful businessman and a dangerous criminal, a pillar of the community and a threat to social order, a victim of violence and a perpetrator of corruption. Understanding his life and death provides insight not only into Reading’s unique criminal history but into the broader patterns of organized crime development during a crucial period in American history.

The twelve years of Tony Moran’s reign as Reading’s vice king represented a golden age of organized crime in the city, when criminal operations achieved unprecedented levels of sophistication and integration with legitimate society. His murder marked the end of this era and the beginning of a more violent and unstable period in Reading’s criminal history, as ambitious successors competed for control of his empire while facing increased federal law enforcement pressure.

Perhaps most significantly, Tony Moran’s story illustrates the human dimension of organized crime history. Behind the statistics about criminal revenues and the dramatic accounts of violent conflicts were real people making complex choices within limited options. Tony’s transformation from Anthony Mirenna to the king of Reading’s underworld reflected not just personal ambition but the social and economic realities of Depression-era America, where traditional paths to success were often blocked and alternative opportunities presented themselves to those willing to take extraordinary risks.

The mystery surrounding Tony’s death ensures that his story will continue to fascinate future generations of historians and crime enthusiasts. Whether Johnny Wittig acted alone out of personal resentment or as part of a conspiracy orchestrated by Abe Minker may never be definitively resolved. But the enduring debate over these questions reflects the broader significance of Tony Moran’s life and death in the history of American organized crime.

In the end, Tony Moran’s legacy lies not in the specific details of his criminal operations or the circumstances of his murder, but in his demonstration that organized crime could function as a sophisticated business enterprise deeply integrated with legitimate society. His success and ultimate failure provide lessons about both the possibilities and limitations of criminal power in American society, making his story an essential chapter in understanding the complex history of organized crime in the United States.

Tony Moran’s legacy is one of contradiction. He was both feared racketeer and respected businessman; a man with few arrests yet enormous criminal reach. His integrated empire of gambling, prostitution, and numbers rackets—combined with political protection—set the model for organized crime in Reading.

His violent end, his refusal to name his killer, and the conspiracy theories that followed ensured his place in Reading’s lore. To some, he was Reading’s “underworld czar.” To others, a symbol of the uneasy marriage between politics and racketeering in mid-20th century Pennsylvania.

The first time I read an in-depth history of Reading’s mafia and lived and worked here most of my life.

Loved this!!! My grandfather would tell me stories of running numbers for Moran and shooting pool in the pool hall…..

Mine too. His stories of being a kid and driving truck or “running errands and numbers” for Tony always fascinated me. I remember “little pope,” some of his other friends when he’d take me to the pool halls when I was a kid in the late 70s and 80s.