The Reading Railroad massacre of July 23, 1877, in which ten people lost their lives, was the climax of local events in Reading, Pennsylvania during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, from which the Reading Railroad was born, was a corporate giant during the 1870s. The Reading’s thirty-six-acre shop complex dominated the downtown area, and 1,500 of the city’s estimated 40,000 residents worked for the company.

Under the iron-fisted rule of its president, Franklin Gowen (February 9, 1836 – December 13, 1889), the Reading gobbled up coal mines, canals, and shipping vessels. Always expanding, and taking huge risks with investors’ millions, Gowen ran roughshod over workers’ attempts to unionize or form benevolent societies to provide benefits for injured workers and their families. An economic depression precipitated by the worldwide financial panic of 1873 assured Gowen and other industry owners of a ready supply of desperate job seekers.

Below: Franklin Gowen.

In the 1860s railroad workers had organized the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and the Workingman’s Benevolent Association to advance their interests. By the mid-1870s, these organizations had become strong enough to threaten Gowen’s iron-fisted control, only to see him crush the Workingman’s Benevolent Association through the infamous “Long Strike” during the cold winter of 1874-1875. Since his railroad controlled all coal transportation in the region, Gowen was able to prevent any individual coal operators from negotiating with the coal miners.

Fresh from vanquishing the Workingman’s Benevolent Association, Gowen learned from his spies that the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers were planning an engineer’s strike in Reading. They had taken earlier pay cuts, even before the Panic of 1873. In the fall of 1876, they took another 10 percent wage cut. Gowen ordered his General Manager, John Wooten, to issue an ultimatum to the engineers: resign from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers or be fired. As a carrot, Wootten offered a company-sponsored accident benefit program. But the Reading engineers did strike, and management filled their positions with non-union labor. Gowen had damaged a second union, but labor’s confidence was building in the face of extreme conditions.

In May 1877, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) also imposed 10 percent pay cuts. A few weeks later, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad ordered 10 percent pay cuts for any worker making more than one dollar a day. Furious B&O workers abandoned their trains at Martinsburg, West Virginia, on July 16, sparking the Great Strike of 1877. The strike spread rapidly, becoming the first nationwide labor action and prompting governors in several states to call out their national guard units as well as, eventually, federal troops to maintain order.

The worst battles took place in Pittsburgh, where rioters burned the PRR’s station, roundhouse, shops, yards, and dozens of locomotives and pieces of rolling stock. National Guardsmen shot and killed more than two dozen people. Elsewhere around the state, mobs halted trains at Philadelphia, Columbia, Harrisburg, Altoona, Johnstown, and Scranton.

On Saturday, July 21, 1877, great excitement prevailed in the city, owing to the general strike of railroad trainmen in the following States: New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri.

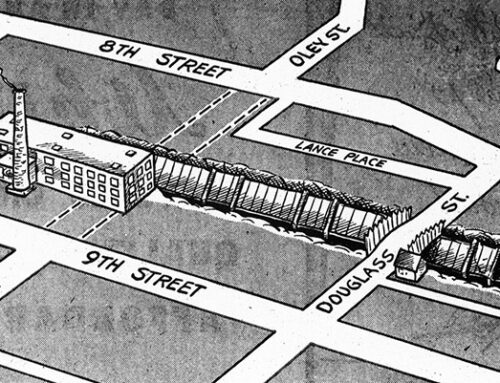

On the night of July 22, rioters burned a car filled with roof shingles was set ablaze on a railroad siding, near the corner of Elm Street and 7th Street. A crowd of over two thousand people took the depot, and burned two cabooses, seven freight cars, and the watch house at the Reading and Lehigh Railroad junction at Bushong’s Furnace. As a result of the ongoing unrest throughout Pennsylvania, the state militia was assembling to travel to the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg, under order of the governor. In order to prevent the militia from reaching the capitol, a group of rioters set fire to the Lebanon Valley Railroad Bridge over the Schuylkill River. The bright flames, which flashed high into the darkness of the night, attracted thousands of people to the place. The bridge was completely destroyed, with only the brick piers remaining. The damage was estimated at $150,000 (equivalent to about $3,500,000 in 2019).

Below: Burning Of The Lebanon Valley Railroad Bridge By The Rioters,” Harper’s Weekly.”

The news shocked the whole community. Crowds had gathered on Saturday, innocently, apparently, but unlawfully, without any earnest movement from the police to disperse them, and property had been destroyed on Sunday. On Monday, the newspapers were almost wholly, taken up with vivid descriptions of the excited condition of the community and of the destructive work of incendiaries. Throughout the day, great excitement prevailed, and as the night approached it grew greater. The four corners of Seventh and Penn streets were again crowded hour after hour, subject to a weak protest; but without any determined effort from municipal or county authorities to clear the highway. Trains were stopped, coal cars detached and many tons of coal dumped upon the track for several hundred feet.

With this state of affairs, the 6 o’clock passenger train approached the city around the bend of “Neversink,” and the shrill whistle of the engine never sounded in such a piercing manner. The engineer remained bravely at his post; the command was given to proceed forward at full speed, and forward indeed he directed his engine at the rate of forty-five miles an hour over the blockaded track. Fortunately the train passed through safely, but the people scattered for their lives, coals were thrown high into the air, and a dense cloud of black dust obscured everything round about for a time. At the passenger station, great excitement arose immediately after the arrival of this train. The next down train was stopped in the cut, and this daring proceeding drew the crowd from the depot and intensified the excitement at Seventh and Penn streets. And the people remained at that point, immovable. Proclamations by the sheriff and earnest appeals by the policemen did not make the slightest impression upon them. The vast multitudes were in sympathy with the riotous demonstrations. And so matters remained for nearly two hours, apparently growing worse as the darkness of night fell upon the community. Then, however, a sudden change arose. And what agent was this that could, as it were, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, separate a maddened, threatening crowd, when sober, sensible appeals to citizens who had theretofore been a law-abiding people, were wholly unavailing? It was the bullet. This acted upon them as effectually as the lightning upon restless, thickening clouds in a portentous sky.

About 8 o’clock, seven companies of the 4th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers, numbering about two hundred men, under the command of Gen. Franklin Reeder, arrived at the railroad station in the city, viz.: Company B, Allen Rifles, Allentown; Company D, Allen Continentals, Allentown; Company E, Blue Mountain Legion, Hamburg; Company F, Easton Grays, Easton; Company H, Slatington Rifles, Slatington; Company I, Catasauqua; Company K, Portland, Northampton county.

After some consultation they were marched down the railroad and through the “cut” toward Penn street to liberate the train there. On the way, they were attacked by persons on the elevated pavements who threw stones and bricks upon them. They did not fire in self-defense, but moved on bravely. Nearing Penn street, the situation became so dangerous that some of the men, by some order or mistaken command, shot off their rifles. Bricks and stones were thrown with increased energy, and many shots followed. The crowd immediately scattered, and men were seen bearing away the wounded and killed. With the dispersing crowd, the soldiers also became disordered, and the companies disorganized. Their conduct was disgraceful, and the whole community, and especially the management of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company, lost confidence in them as a means of restoring order or preserving peace. A battery of United States Regular Artillery, equipped as infantry, then came here shortly afterward, under the command of General Hamilton, and remained until peace, order and safety were assured. The fidelity of G. A. Nicolls and George Eltz as officials of the railroad at this point, in the perilous situation of affairs then existing, was highly commendable.

This riot resulted in the killing of ten citizens (Milton Trace, James J. Fisher, Ludwig Hoffman, John H. Weaver, Lewis A. Eisenhower, John A. Cassidy, John A. Wunder, Daniel Nachtrieb, Elias Shafer and Howard Cramp) ; and the wounding of twenty-seven persons (including four policemen) and twelve soldiers.

Below: Reading’s Seventh Street cut looking North from Penn Street, scene of the bloody shooting in July of 1877 when 10 bystanders were slain by militia troops. The firing came when the soldiers entered the cut from north end (seen here in the distance), and somebody in the crowds atop the walls alongside the cut began tossing rocks at the troops.

Dr. George S. Goodhart, the coroner of the county, then held an inquest to inquire into the loss of life; and after hearing a number of witnesses reported on Aug. 7, 1877, that the death of the persons named was caused by the military who were here by direction of the State authorities firing upon the rioters, and the terrible tragedy was directly attributed to the lawless assembling of persons at Seventh and Penn streets.

Many men were arrested and indicted for alleged implication in this riot. Two of them pleaded guilty and were sentenced to imprisonment for five years. There was a hotly contested trial of another, from Oct. 2nd to the 6th, but he was acquitted. The following week, fourteen were tried and all were acquitted excepting one, who was convicted of inciting to riot; and the third week, forty were called for trial but the prosecution was abandoned. These trials caused great excitement. F. B. Gowen, the president of the P. & R. R. Co., conducted the prosecution of these cases in person.

In the aftermath of the strike and massacre, Franklin Gowen pointedly avoided mention of the strike and shootings, although local sympathies for the strikers remained strong. On January 1, 1878, the city of Reading hosted the first national assembly of the Knights of Labor, which in the year that followed grew into the nation’s largest industrial union, and organized national campaigns for the worker benefits and rights.

In 1883 Gowen left his post as president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad and returned to his private law practice. Gowen appeared to be doing well but on 13th December, 1889, he locked himself into his hotel room and committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

Below: Looking southward along the Schuylkill River toward the Lebanon Valley Railroad Bridge in 1897. The bridge was rebuilt following the 1877 railroad riots. Part of the original abutment is visible beside the present one along the present-day West Shore By-Pass (near the cow trail on right side of photo). The Keystone furnace (left side of photo) was erected in 1869, and used for the manufacture of pig iron.

Leave A Comment