The Gentleman Bootlegger Who Defied Every Stereotype

In the violent, chaotic world of Prohibition-era organized crime, Max Hassel stood apart as an anomaly—a bootlegger who built his empire through business acumen rather than bullets, charity rather than cruelty, and political sophistication rather than street-level intimidation. Known as “The Millionaire Newsboy,” Hassel rose from immigrant poverty in Reading, Pennsylvania, to become one of America’s most successful beer barons, only to meet a tragic end when he tried to go legitimate. His story reveals the complex contradictions of the Prohibition era and offers a fascinating glimpse into how one man transformed criminal enterprise into community leadership.

From Immigrant Struggle to American Dream

Max Hassel’s story began in the poverty and persecution of Eastern Europe, but it was shaped by the opportunities and contradictions of early 20th-century America. Born Mendel Gassel on April 24, 1900, in Dvinsk, Latvia (then under Russian rule), he was part of the great wave of Jewish immigration fleeing the harsh conditions of Czarist Russia.

The family’s journey to America unfolded in stages, as was common for immigrant families of limited means. His father Elias arrived in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1908 with his eldest daughter Fannie, establishing a small tailoring business while saving money to bring the rest of his family to the New World. The separation lasted three painful years until September 1911, when Sarah and her four children—including 11-year-old Mendel—finally arrived at Ellis Island aboard the S.S. Kursk.

In a remarkable historical coincidence, Meyer Lansky, who would later become one of organized crime’s most powerful figures, had arrived on the same ship just six months earlier. The two boys’ paths would cross dramatically decades later, when Lansky would play a role in ordering Max’s assassination.

Upon arriving in Reading, young Mendel immediately began the process of Americanization that would define his character. He anglicized his name to Max Hassel, though he would spend years trying to legally formalize this change. Unlike many immigrant children who struggled with the cultural transition, Max excelled, demonstrating an early aptitude for commerce and an instinctive understanding of American entrepreneurship.

Early Entrepreneurial Genius

Max’s business instincts manifested remarkably early. At age 14, he left school to become a cash boy at Pomeroy’s, Reading’s largest department store—a common entry-level position for young men of his era. Even then, his exceptional abilities were evident. George Pomeroy, the company’s co-founder, selected Max from among numerous cash boys to serve as his personal messenger, an unprecedented honor that spoke to the teenager’s reliability and intelligence.

But Max wasn’t content to remain an employee. After leaving Pomeroy’s, he became a Reading Telegram newsboy, where customers remembered him for his politeness and lightning-fast change-making abilities. His nickname “The Millionaire Newsboy” would later honor these humble beginnings, but even as a teenager, Max was planning bigger things.

At 16, he took his first major entrepreneurial gamble, leaving steady employment to start a cigar-making business with his friend Israel “Izzy” Liever. Their company, Berks Cigar Company, operated out of a cramped second-story room, but it was profitable enough to spawn a second venture, Universal Cigar Stores. By age 19, Max had established a chain of cigar stores and built up an impressive $30,000 line of credit with local banks—a substantial sum for a teenager in 1919.

These early ventures revealed the characteristics that would define Max’s entire career: meticulous attention to quality, innovative business practices, and an extraordinary ability to build relationships with influential people. More importantly, they demonstrated his talent for organization and his willingness to take calculated risks.

Prohibition: The Golden Opportunity

When the 18th Amendment banned the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in 1920, most Americans saw either moral victory or unfortunate restriction. Max Hassel saw the business opportunity of a lifetime. Unlike many bootleggers who were already established criminals when Prohibition began, Max came to the trade as a legitimate businessman seeking to expand his operations into a new, highly profitable market.

His entry into bootlegging was characteristically sophisticated. In 1920, he established the Schuylkill Extract Company, obtaining a federal permit to withdraw industrial alcohol for “food extract” production. This legal loophole allowed him to acquire thousands of gallons of alcohol monthly, which he then diverted to illegal sales. When authorities became suspicious, Max demonstrated the pragmatic flexibility that would mark his entire career—he simply surrendered his permit and walked away with his $20,000 bond intact.

Undeterred by this setback, Max soon returned to the alcohol business under an assumed name, forming Berks Products Company with a fictitious president named Stanley Miller. When this operation was also discovered, Max again escaped serious consequences, receiving only a citation and permit revocation. These early experiences taught him valuable lessons about legal protection and the importance of maintaining plausible deniability.

The Beer Baron’s Empire

Max’s real fortune came from beer, not hard liquor—a strategic decision that would make him one of America’s most successful bootleggers. As he transitioned from alcohol to beer production, he demonstrated the sophisticated strategic thinking that separated him from common criminals.

Rather than competing with established breweries, he began acquiring them, starting with the financially troubled Fisher Brewery in 1921. The Fisher acquisition revealed Max’s sophisticated understanding of corporate structure and legal protection. He purchased the brewery through a Delaware corporation called Brazilian Aramzem, with William Abbott Witman Sr. serving as a straw owner until the necessary licenses were obtained. Once operational, Max initiated a bewildering series of title changes involving multiple dummy buyers, making it virtually impossible for authorities to trace actual ownership.

By 1923, Max controlled three major breweries in Reading: Fisher, Lauer, and Reading Brewing Company. His method was ingenious—he offered brewery owners attractive lease arrangements that transferred all operational risk to him while providing them with steady rental income. The breweries operated by producing both legal “near beer” (with less than 0.5% alcohol) and illegal real beer (typically 3-4% alcohol) simultaneously.

The profits were staggering. Beer that cost $2.50 per half-barrel to produce sold for $8-10 wholesale and $11-16 to speakeasies. With such margins, Max quickly became Reading’s most prominent bootlegger and one of the wealthiest men in the city. By the time he was 25, he had become a millionaire—an extraordinary achievement in the 1920s.

Master of Legal Evasion

What truly set Max apart from other bootleggers was his ability to avoid conviction despite constant government attention. Between 1922 and 1933, he was arrested multiple times on charges ranging from bribery to tax evasion, yet he never spent a single day in jail.

His legal strategy involved hiring the best attorneys money could buy, many with significant political connections. His defense team included Congressman Benjamin M. Golder, future Congressman Robert Grey Bushong, and former Pennsylvania State Senator John R.K. Scott. These weren’t just skilled lawyers—they were power brokers who understood how the political system worked.

Max’s most famous legal victory came in his 1929 tax settlement. The government claimed he owed $1.24 million in unpaid taxes on income exceeding $2 million between 1920-1924. Through skilled negotiation, Max settled for just $150,000, with no jail time and a guarantee that the settlement wouldn’t be used against him in future proceedings. This settlement demonstrated both his wealth and his ability to negotiate with federal authorities as an equal.

The Philanthropic Paradox

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Max Hassel’s career was his unprecedented commitment to charity. In an era when bootleggers were known for violence and excess, Max became Reading’s most generous benefactor. His charitable activities were so extensive and well-known that they became central to his public identity.

Max’s philanthropy took many forms, each revealing different aspects of his character:

Holiday Giving: Every Thanksgiving and Christmas, Max sent trucks loaded with food and gifts through Reading’s streets. Charlie Marks, one of his associates, distributed supplies to needy families, with no questions asked about religion or background.

Education: Max paid college tuition for numerous young people and regularly attended school pageants and lectures. Thomas J. Evans, president of the Reading Board of Education, testified that Max had genuine interest in child development and education reform.

Anonymous Donations: Much of Max’s giving was done secretly. George Pomeroy Jr. testified that Max regularly sent orphans to Pomeroy’s department store to be outfitted with clothes, with strict instructions that the children never learn who was paying.

The Hassel Free Loan Society: After his father’s death in 1930, Max established this organization with a $15,000 endowment to provide interest-free loans for education and family emergencies.

The scale of Max’s giving was extraordinary. By some estimates, he distributed over $20,000 annually to political campaigns alone, and his total charitable contributions may have exceeded his personal living expenses. This philanthropy wasn’t mere public relations—Max genuinely cared about his community and saw his wealth as carrying social responsibility.

The Gentleman’s Style

Max’s personal style set him apart from the stereotypical bootlegger image popularized by Hollywood. Standing about 5’4″ and always impeccably dressed, he was known for changing his expensive fedora hats almost daily, often giving barely-worn hats to friends and employees. His suits were custom-tailored, and while he wore substantial diamond jewelry, it was always done tastefully.

Despite his wealth, Max maintained strong family ties and traditional values. He lived with his parents until their deaths and was devoted to his siblings. He never married, though he maintained long-term relationships and was known to be generous with his romantic interests.

Max was also a fitness enthusiast, unusual among bootleggers of his era. He installed a complete gymnasium in his later headquarters and tried unsuccessfully to convince his associates to maintain their physical health. He was an avid golfer, though admittedly not a skilled one, and enjoyed card games, particularly pinochle.

Moving to the Big Leagues

By 1928, federal pressure on Max’s Reading operations had intensified significantly. Governor Gifford Pinchot, an ardent prohibitionist, had ordered Pennsylvania State Police to crack down on bootleggers. After a series of devastating raids that cost Max millions in lost product and damaged equipment, he made the fateful decision to expand into North Jersey.

In July 1929, Max leased a suite at the Carteret Hotel in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and entered into partnership with two of the most powerful bootleggers in America: Waxey Gordon and Max “Big Maxie” Greenberg. This trio would control what the government later estimated to be sixteen or seventeen breweries stretching from Buffalo to Delaware.

The partnership brought Max into contact with the highest levels of organized crime. The Gordon-Hassel-Greenberg combine was one of the largest beer operations in the country, supplying much of New York City’s demand for real beer. However, it also placed Max in the crosshairs of rival gangs and federal investigators.

The Commission’s Opposition

As Prohibition neared its end, the organized crime families faced a crucial question: how to maintain their power and profits in a legal alcohol market? The answer, developed by Lucky Luciano’s Commission, was to establish tribute systems that would tax both legitimate and illegitimate alcohol operations.

Max Hassel had different plans. Unlike his criminal associates, he genuinely wanted to become a legitimate businessman when Prohibition ended. He had already obtained federal licenses for several of his breweries to produce legal 3.2% beer when it became legal in April 1933. His goal was to transition from bootlegger to respected brewer, paying taxes to the government rather than tribute to the mob.

This decision put him on a collision course with The Commission. Luciano, Meyer Lansky, and other mob leaders viewed Max’s planned legitimacy as a direct threat to their post-Prohibition strategy. If successful bootleggers could simply “go straight,” it would undermine the entire organized crime structure they were building for the future.

The Final Day

The end came suddenly on April 12, 1933. Max was in his suite at the Carteret Hotel with Waxey Gordon, Big Maxie Greenberg, and several associates, discussing the growing threats from Dutch Schultz and other New York gangsters who wanted to muscle in on their territory.

At approximately 4:30 PM, two gunmen entered the suite and opened fire without warning. Max Hassel was shot three times in the back of the head while trying to flee toward the office doorway. Big Maxie Greenberg was shot five times in the chest and head while slumped over a desk. The killers escaped down a rear staircase, leaving behind only a .38 caliber pistol and two dead bodies.

The murders sent shockwaves through both the underworld and legitimate society. For Reading, it was the end of an era. More than 15,000 people lined the streets to view Max’s body at the funeral home, and his funeral procession included over 100 cars—possibly the largest in the city’s history.

The Confession

For almost seventy years, the identity of Max Hassel’s killers remained a mystery. Then, in 2001, a remarkable revelation emerged. Joe Stassi, a 94-year-old former gangster living in Florida, admitted to writer Richard Stratton that he had been ordered by Meyer Lansky, Abe Zwillman, and Joe Adonis to kill his best friend.

Stassi’s confession, published in Gentleman’s Quarterly, revealed the personal anguish of a man forced to choose between friendship and survival. Though he never explicitly said “I killed Max Hassel,” his emotional account left little doubt about his role in the murder.

According to Stassi, The Commission ordered the hit because Max’s determination to go legitimate threatened their plans to control the post-Prohibition alcohol industry. The irony was devastating—Max died not because he was a criminal, but because he wanted to stop being one.

Reading’s Reaction and Legacy

The massive outpouring of grief at Max’s funeral revealed Reading’s complex relationship with its most famous criminal. An estimated ten thousand mourners packed a two-block area of North 5th Street as they waited in line to view his coffin. This wasn’t just curiosity—it was genuine mourning for a man who had become a pillar of the community despite his illegal activities.

The size and emotion of the crowd revealed several important aspects of Max’s relationship with Reading:

- Economic Impact: Many mourners owed their livelihoods directly or indirectly to Max’s operations during the Depression

- Community Integration: Unlike many criminals, Max had become a respected member of the community

- Public Sympathy: Many residents viewed Prohibition as unjust and saw Max as a businessman rather than a criminal

- Personal Relationships: Max had cultivated genuine friendships and loyalties throughout the community

The Power Vacuum

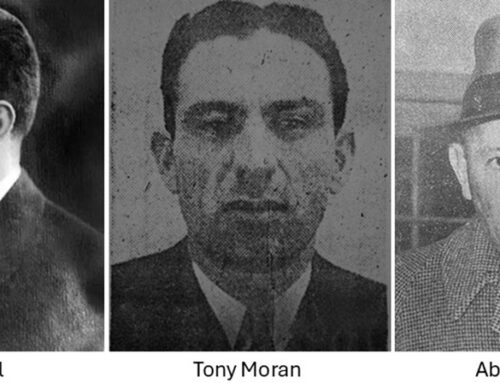

Max’s death created a significant power vacuum in Reading’s underworld, leading to a period of instability and violence as various figures scrambled for control. Tony Moran, born Anthony Mirenna, gradually emerged as a prominent figure in the city’s rackets, though his ascent was less meteoric than Max’s and his activities were less well-documented.

Moran controlled a substantial portion of the numbers game, oversaw a network of brothels, and dabbled in the slot machine business. However, he never achieved Max’s level of community integration or political influence. In 1945, Moran was shot and killed in his own gambling den, continuing the cycle of violence that had claimed Max twelve years earlier.

The Hassel Foundation Legacy

Max Hassel’s charitable legacy continues today through the Hassel Foundation, established in 1961 by Max’s siblings. With assets exceeding $7 million, the foundation continues Max’s tradition of supporting education, health services, and community development, particularly in Jewish organizations.

This lasting institutional legacy is perhaps Max’s greatest achievement—proof that his philanthropy was genuine rather than mere public relations. The foundation’s continued operation nearly a century after Max’s death demonstrates the depth of his commitment to community service.

Lessons from the Beer Baron

Max Hassel’s story offers profound insights into organized crime, political corruption, and the unintended consequences of Prohibition:

About Criminal Enterprise: Max proved that business acumen could be more valuable than violence in building criminal organizations. His professional approach, focus on quality, and emphasis on customer service created a more sustainable and profitable operation than the violent territorial wars that characterized many bootlegging operations.

About Community Relations: Max demonstrated that economic benefits and genuine community involvement could overcome moral objections to illegal activities. His integration into Reading society provided protection that intimidation could never achieve.

About Political Corruption: Max’s systematic approach to bribing officials became a template copied by organized crime figures for decades. He understood that corruption was an investment in business infrastructure rather than just a cost of doing business.

About Prohibition’s Failure: Max’s success illustrated how unenforceable laws create opportunities for organized crime. When millions of Americans wanted a product that was illegal but not immoral, entrepreneurs like Max filled the market gap.

The Hassel Method

Max Hassel’s approach to organized crime became a model that influenced criminal enterprises for generations. His methods included strategic planning, relationship management, operational excellence, and community integration. Unlike criminals who relied on fear and violence, Max built his empire on reliability, quality, and mutual benefit.

This “Hassel Method” proved that organized crime could be conducted as a business enterprise rather than a purely predatory venture. His techniques influenced generations of criminals who learned that corruption, community integration, and professional operations could be more effective than violence and intimidation.

The Tragic Irony

The ultimate irony of Max Hassel’s life was that his death came not from his illegal activities but from his attempt to become legitimate. This tragic end highlighted the difficulty faced by successful criminals who tried to transition to legal enterprises. The organized crime networks that had benefited from partnerships with bootleggers were not willing to let valuable assets simply walk away.

Max’s murder marked the end of the relatively genteel era of Prohibition bootlegging and the beginning of a more violent phase in organized crime. His death demonstrated that the criminal world had become more territorial and unforgiving, unwilling to allow successful members to retire to legitimate businesses.

Conclusion: The Bootlegger’s Complex Legacy

Max Hassel’s life embodied the central contradictions of the Prohibition era. He was simultaneously a criminal who violated federal law on a massive scale and a businessman who provided a product that millions of Americans wanted. He was a corruptor who undermined law enforcement and a pillar of the community who supported charities and provided employment during the Depression.

His story reveals the complex relationships between crime, business, politics, and community during one of the most fascinating periods in American history. He was neither a simple criminal nor a folk hero, but something more complicated: a successful entrepreneur whose business happened to be illegal.

Max proved that during Prohibition, the line between criminal and legitimate businessman was often thinner than government officials wanted to admit. His success demonstrated that when laws conflict with popular demand, entrepreneurs will emerge to serve that demand regardless of legal consequences.

In Reading, Max Hassel is still remembered not primarily as a criminal, but as a folk hero who defied unjust laws while genuinely caring for his community. His massive funeral demonstrated that he had achieved something rare among criminals: he became a respected member of society whose illegal activities were forgiven because of their perceived benefits to local residents.

Max Hassel’s greatest achievement may have been proving that organized crime could be conducted with honor, generosity, and community responsibility. His tragic end serves as a reminder that in the criminal world, success can be as dangerous as failure, and that the transition from crime to legitimacy is fraught with perils that even the most successful criminal entrepreneurs cannot fully control.

The story of “The Millionaire Newsboy” remains a compelling chapter in American organized crime history—a tale of immigrant ambition, entrepreneurial genius, and the deadly contradictions of an era when the law failed to match the will of the people.

Leave A Comment