The Lindbergh Viaduct was constructed to provide another eastern entrance to the City so as to relieve Perkiomen Avenue of some of its traffic. Built in 1927 at a cost of about $470,000, the Viaduct was designed by Berks County Engineer Charles F. Sanders, and was the first concrete Viaduct built on a curve in the United States.

Efforts to construct the span started in the early 1900s. The Reading Chamber of Commerce, meeting with City Council, the City planning commission, Mount Penn Council, officers of the nearby Aulenbach Cemetery and the Reading Transit and Light Co., began advocating such a traffic artery in 1920.

On Feb. 2, 1927, bids were opened for the construction of the Lindbergh Viaduct. Fifteen bids for the construction of the Viaduct were received by City Council. The contract was awarded to Whittaker & Diehl, of Harrisburg.

The Viaduct was provisionally known as the Mineral Springs Road Viaduct. Its name was changed on June 15, 1927 when City Council dedicated the Viaduct in honor of famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh who completed his solo transatlantic flight that year.

Built on a sweeping horizontal curve, it forms a backdrop to Reading’s Pendora Park. The Viaduct, a 13-span, reinforced-concrete, open-spandrel arch Viaduct, is 563 feet long, and is 70 feet wide, thus providing for a roadway of 50 feet and sidewalks of 10 feet each on both sides. The western end of the Viaduct is located on Mineral Spring road east of Eighteenth Street. The eastern end passes over Rose Valley Creek, a section of Pendora Park and South 19th Street, and meets the hillside at a point near where a station for the Mount Penn gravity railroad once stood.

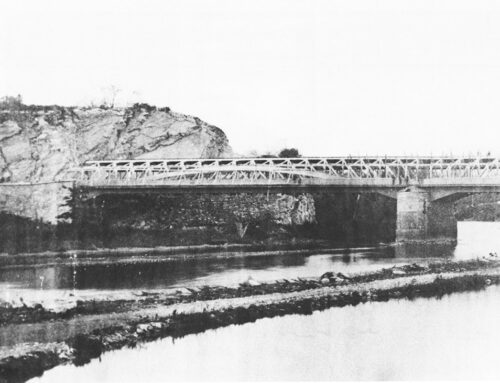

Below: Mineral Park Gravity Railroad Station.

The Viaduct opened for pedestrians around February, 1928. Hundreds of people crossed the Viaduct the first day. It opened to vehicular traffic on Memorial Day 1928.

A fight for another name for the Viaduct followed its opening when Lindbergh, the American hero of the flight to Paris, fell in disfavor in 1940 for his isolationist attitude.

On Nov. 18, 1940, the Polish-American Democratic Assn. proposed to City Council that the Viaduct be named in honor of a “true American hero”…Count Pulaski, the Polish patriot who fought with the American revolutionists.

On Nov. 27, 1940, Council got more suggestions for a name, including “Victory Viaduct.”

Council discussed other suggestions and then shelved them.

Nothing more was apparently heard until Feb. 15, 1942. Mayor Harry F. Menges prepared a resolution to change the name of the span to MacArthur Viaduct,” in honor of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, hero of Bataan. The proposal received no favorable comment so he decided to hold his resolution.

A bronze plaque located on the eastern side of the Viaduct bears the following inscription:

This structure provisionally known as Mineral Spring Road Viaduct is dedicated as a monument to Col. Charles A. Lindbergh and his memory as a pioneer, non-stop New York to Paris aviator, by resolution of City Council June 15, 1927.

The words are inscribed under a map outlining the Spirit of St. Louis path across the Atlantic.

The 85 year-old Viaduct has been rehabilitated twice, in 1970 and 2003. Six spans were removed during the 2003 rehabilitation. The removed spans were replaced with reinforced concrete pavement supported on fill. The remaining 7 spans were rehabilitated and restored to their original design.

The Viaduct was posted to the National Register of Historic Places on June 22, 1988.

Construction of the Lindbergh Viaduct brought with it the abandonment of most of the Mineral Spring trolley, line, which at one time curved around a duck pond to the nearly forgotten Mineral Spring Park located just north of the Viaduct in Rose Valley. The trolley line along Nineteenth Street from Perkiomen Avenue was torn up. No provisions were made to re-establish a trolley line to the park entrance.

No longer were picnickers able to ride in trolley cars to the entrance to Mineral Spring Park. The nearest trolley line was on Perkiomen Avenue. Families without automobiles were compelled to travel over rough and stony roads from Nineteenth Street and Perkiomen Avenue, a distance of about three blocks, before they reached the entrance to the park. Cut off from trolley transportation and no longer conveniently accessible to automobile traffic, the popularity of Mineral Spring Park dwindled down.

Interesting facts…

- The bronze plaque has disappeared twice. In 1966, the tablet was found in Pendora Park. In 2002, police seized the plaque at MaryAnn’s Antiques & Collectibles at the Fairgrounds Farmers Market in Muhlenberg Township. A woman claimed she found the plaque in her father-in-law’s basement, where it had been used to keep coal from spilling out of a bin. The woman claimed she didn’t know how her deceased father-in-law acquired the plaque.

- 18,000 and 22,000 barrels of cement were used for the construction of the Viaduct.

- Ghosts of suicide victims are said to patrol the Pendora Park region of Reading, Berks County. The Viaduct has seen a handful of deaths and several witnesses have reported terrifying screams and shadowy figures plummeting from the structure.

Leave A Comment