In the woodlands south of Reading, Pennsylvania, the landscape around French Creek tells two quintessentially American stories. One is the 18th–19th-century tale of Hopewell Furnace—an industrial community of ironmasters, colliers, founders, and teamsters who helped forge a young nation. The other is the 20th-century story of Camp Hopewell—an early home for Berks County Scouts run by the Daniel Boone Council (formerly the Reading-Berks County Council), which set the stage for today’s Hawk Mountain Council camping program. Together, these stories chart a remarkable transformation: from a working iron plantation, to a reforested public playground, to a carefully preserved historic site where visitors can still read the layers of industry, conservation, and youth camping on the land itself.

Hopewell Furnace: A Working Industrial Landscape (1771–1883)

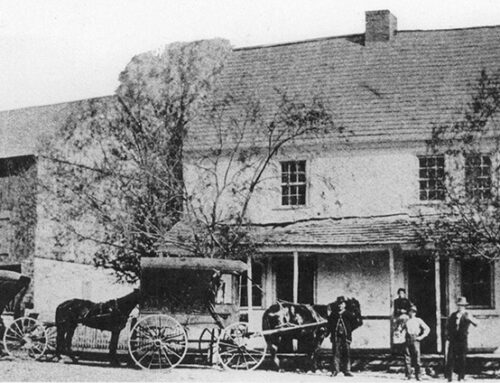

Hopewell Furnace began operating in 1771 as a classic charcoal-fueled “iron plantation,” a self-contained enterprise that coupled blast furnace, casting house, and ancillary shops with housing, orchards, and woodlots. The operation’s heartbeat was the forest: teams of colliers burned cordwood in earthen kilns to make the charcoal that fed the stack, while wagoners and teamsters moved ore, flux, fuel, and finished castings along primitive roads. Across more than a century of smelting—through the Revolution, the Early Republic, and the rail-driven 19th century—Hopewell’s demand for charcoal repeatedly cleared and then regrew the surrounding hills, leaving an ecological and visual pattern still legible in the maturing woods of French Creek today.

By the late 1800s, as ironmaking modernized, anthracite and then coke replaced charcoal and centralized furnaces eclipsed small plantations. Hopewell’s charcoal stack, like many of its kind, could not compete with the scale and fuel efficiency of the new order. Operations ceased in 1883. Buildings slumped into disrepair, fields went to seed, and the industrial village faded into memory—its future uncertain until a national crisis brought a new stewardship.

Hopewell Furnace

New Deal Preservation and the Birth of a Park (1930s–1940s)

During the Great Depression, the federal government assembled large tracts around French Creek and Hopewell, pairing land acquisition with the labor of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The CCC’s dual mission—put men to work and rebuild the land—suited French Creek perfectly. Enrollees stabilized eroded slopes, planted trees, and laid out a recreation network: new roads and trails, picnic grounds, group camps, tent sites, and two impoundments with beaches that would soon anchor warm-weather crowds. At the same time, conservation planners began to stabilize and restore the furnace village itself, recognizing Hopewell’s national significance as an intact example of the charcoal-iron era.

Out of this effort grew a paired legacy: French Creek State Park, a reforested playground designed for public use, and Hopewell Village National Historic Site (today Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site), dedicated to interpreting the technologies, labor, and lifeways of the iron plantation. The CCC left more than facilities—it left a model of landscape care that made room for both recreation and history.

French Creek State Park

Camp Hopewell: A New Home for Scouting (1939–1946)

As the park took shape, Pennsylvania—backed by federal support—made parcels around the new lake available for organized youth camping. In 1939, the Daniel Boone Council (the Reading council founded in 1916, renamed Reading-Berks County Council in 1919, and adopting the Daniel Boone name in 1937) established Camp Hopewell on this state-loaned ground. Girl Scouts and Camp Fire groups soon set up nearby camps, turning the French Creek uplands into a constellation of youth programs.

Troop 150, Hyde Park, at Camp Hopewell, mid 1940s.

State regulations kept the experience intentionally rugged: tents without platforms, patrol cooking instead of centralized mess, and a program that doubled down on the patrol method, woodcraft, and unit self-reliance. Berks County troops thrived in this setting. Period photographs show Hyde Park Troop 150 and many others hiking the ridges, testing lashings in canvas camps, and learning leadership by doing. Over eight summers, approximately 5,000 Scouts cycled through Camp Hopewell—an impressive run that helped define a local Scouting identity grounded in the outdoors.

Camp Hopewell Badge

The model changed in 1946. As French Creek broadened public access to camping areas, the state ended the “loaned” Scout camp arrangement. Without a dedicated reservation for summer operations, the council suddenly had to improvise—weekending locally and sending units to other councils’ camps or to national training grounds such as the BSA’s Schiff Scout Reservation—until a permanent solution could be built.

After Hopewell: The Road to Shikellamy (late 1940s–1950s)

The end of Camp Hopewell catalyzed the council’s long-term vision. Between 1948 and 1951, the Daniel Boone Council assembled land on the south slope of Blue Mountain and opened Camp Shikellamy. There the council created a purpose-built reservation with a lake, dining facilities, program areas, and an infrastructure that supported larger, more centralized summer operations. Many traditions that would later define Berks-Schuylkill Scouting took root on this mountainside.

From Two Councils to One: The Hawk Mountain Era (1970–present)

In 1970, the Daniel Boone Council (Reading/Berks) and the Appalachian Trail Council (Schuylkill) merged to form the Hawk Mountain Council. Camping consolidated at the former Blue Mountain Scout Reservation, which—after redevelopment and significant investment—was rededicated in 1978 as the Hawk Mountain Scout Reservation. From waterfronts and ranges to dining hall songs and staff traditions, the modern council’s camping culture descends directly from the improvisation forced by Hopewell’s closing and the permanent base built at Shikellamy.

Councils at a Glance (as they relate to Hopewell)

- Reading Council (1916) → Reading-Berks County Council (1919) → Daniel Boone Council (1937): Operated Camp Hopewell (1939–1946); later developed Camp Shikellamy (opened 1951).

- Appalachian Trail Council (Schuylkill County): Operated Blue Mountain/Camp Nisatin; merged in 1970.

- Hawk Mountain Council (1970–present): Formed by merger; consolidated camping at Blue Mountain and rededicated it as Hawk Mountain Scout Reservation (1978).

Key Dates at a Glance

- 1771–1883: Hopewell Furnace operates as a charcoal iron plantation.

- 1930s: Federal government purchases land; CCC builds recreational infrastructure and begins furnace restoration.

- 1939: Daniel Boone Council opens Camp Hopewell on state-loaned land.

- 1939–1946: ~5,000 Scouts camp at Hopewell.

- 1946: Camp Hopewell closes as the park shifts to general public camping.

- 1951: Daniel Boone Council opens Camp Shikellamy.

- 1970: Daniel Boone Council and Appalachian Trail Council merge to form Hawk Mountain Council.

- 1978: Blue Mountain Reservation rededicated as Hawk Mountain Scout Reservation.

Leave A Comment