In 1893, David Rosenbaum constructed one of Reading’s most exquisite and ornamental structures.

Mr. Rosenbaum moved to Reading in 1882 and purchased the property at 702 Penn Street and the southeast corner lot at Seventh and Penn Streets, where he founded his Clothier and Hatter business. The company became a recognized leader in its local trade departments, both in terms of volume of solid business, range of attractions, and consistent product reliability. Rosenbaum established a huge and profitable business via hard work and attention to detail.

Below: Sketch of Rosenbaum Clothier and Hatter building, 702 Penn Street, 1882.

Rosenbaum’s massive business in men’s and boys’ custom and ready-made apparel, hats, and furnishings grew to the point where he couldn’t find enough space to display his products. Instead of enlarging the building at 702 Penn Street, he decided to demolish it and build a new four-story commercial structure.

Rosenbaum moved his firm to 714 Penn Street to begin building on his new location. The new building, planned by architect Alex. F. Smith and built by contractor L. H. Focht, had a 26-foot frontage and a depth of 97-1/2 feet. The architectural style was Romanesque, with rounded French roofs and a magnificent tower at the top. The five-story house, constructed of pressed brick with sandstone and Warsaw blue-stone embellishments, had a deep basement. The structure served as a testament to the foresight of one of Reading’s most successful businesses.

On the Penn Street front and along 7th Street for 26 feet, the outside architectural style was identical, with elegantly constructed bay windows, double windows, and a tower crowned by a flagstaff at the top. The big bulk windows on the first level provided opportunities for magnificent presentations. The gables’ copings and finals were made of terracotta. The upper half of the tower was made of copper with tin shingles in the style of Spanish tiling. The flat roofs were tinned, while the slope elements of the roof and gables were made of slate. The interior woodwork was all hardwood, with polished yellow pine flooring of extraordinary beauty and strength.

The building was dedicated on December 4, 1892, with the grand opening of the clothing and furnishing store, which took up the entire first level. Three thousand souvenirs were distributed among the visitors who came to inspect the store and congratulate Mr. Rosenbaum. The ladies were given lovely embossed cards, while the males received unique match safes in the shape of a pair of trousers. These were depleted well before the store closed, and the estimated attendance ranged between five and six thousand people.

The second floor was divided into five offices with private rooms, the third floor served as a club area, and the fourth housed the Red Men Society. A broad hallway on Seventh Street served as the entrance to the upper stories.

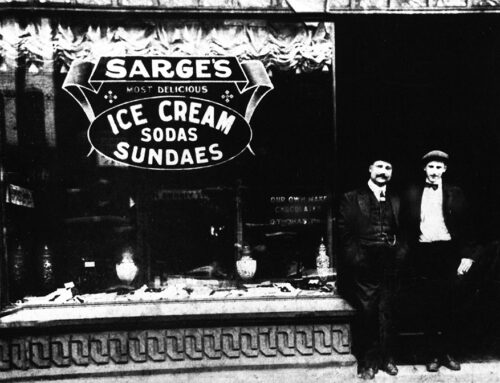

Rosenbaum’s was sold in 1906 and renamed Sondheim’s.

Reading suffered during the Great Depression as a result of the declining purchasing power and reduced expenditure of the underemployed and unemployed. The Depression also had an impact on Reading’s main commercial thoroughfare, densely packed Penn Street. In the 1930s, it suffered from the same fiscal and physical illnesses that afflicted so many Main Streets at the time: a cycle of storefront and building occupancy and abandonment, as well as a rotation of stores and other establishments going in and out of operation. By 1931, the impact of the economic crisis was clear in Reading, with notices declaring bankruptcies, expired leases, and merchandise reductions progressively appearing on Penn Street shop fronts. Seven out of fifteen stores on the north side of the 600 block had gone out of business, including the well-known Victor Jewelry, whose “Pay Me Pay Day” sales slogan, spelled out on a two-story flashing marquee, must have seemed like a bitter reminder of more prosperous times to Reading’s unemployed. Nearby, Keystone Meat said that it will “redeem unemployment vouchers” supplied by clients in lieu of cash payment, which better reflects current situations.

Reading merchants must have been equally furious as they watched national chains prosper, seemingly at their expense, in what had become an all-too-familiar retail fight between insiders and outsiders. As the Depression progressed, most local retailers’ efforts proved ineffective in the face of chain development. In a single retail category, for example, chain five-and-dimes such as Woolworth’s, Kresge’s, and McCrory’s increased their market share to 89 percent of all variety store business in Reading, with the five surviving independents fighting to survive on the remaining 11 percent. While this disparity was caused in part by the chains’ low costs, it was also owing to the chains’ ambitious store refurbishment initiatives, which kept their units up to date in order to stimulate sales amid the economic slump.

Sondheim’s clothes store at 700 Penn Street was forced to close in 1933. A.S. Beck Shoes took over the building’s street level and modernized it, despite the chain’s usual flamboyance, with a restrained porcelain enamel design by New York architect Horace Ginsbern.

Funding for the modernization of the storefront was made possible by the Modernization Credit Plan with the passage of the National Housing Act and the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration in the summer of 1934. The goal of the Modernization Credit Plan was to stimulate building activity in order to prime the pump for broader economic recovery from the Great Depression which left its mark on Main Street businesses of Reading.

Below: The Southeast corner of Seventh and Penn streets showing modernized storefront of A.S. Beck Shoe Store.

The war effort, which eventually brought increased production and jobs back to Reading’s factories and mills, was obviously beneficial to downtown retailers. However, once the peacetime economy was fully operational in the years after 1945, Reading’s workers stopped spending their salaries only in Penn Square. The decentralization that begun prior to the war was exacerbated by postwar suburbanization in the shape of interstates, subdivisions, shopping centers, and malls. As these extended throughout the United States, the historic center’s dominance waned in the 1950s and 1960s.

At the time, decentralization was not limited to shopkeepers and households; industry was also decentralizing, with equally devastating effects for Main Street merchants and downtowns as a whole. In Reading, manufacturers who had been the city’s economic mainstay for decades, such as the Reading Hardware & Butt Works and the Berkshire Knitting Mills, began to relocate or shut down entirely, leaving Penn Square with fewer potential customers and surrounded by underutilized factories. The federal government, like it had done in the 1930s, extended downtown help once more. Instead of “modernization,” “urban renewal” was proposed as the cure-all of the moment. The Housing Act of 1949 empowered cities with financing to acquire and eradicate slums for rehabilitation by private developers.

In many downtowns, however, urban regeneration resembled suburban imitation, and Reading was no exception. Buildings on the 600 and 700 blocks of Penn Street were scheduled for demolition, to be replaced by an enclosed shopping mall.

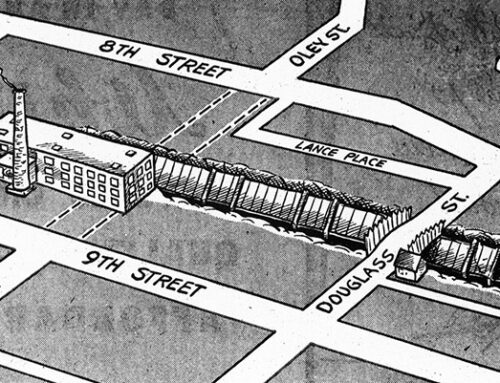

Below: Architect’s rendering of Penn Mall envisioned in the early 1970’s.

Although the project was never completed, numerous buildings in the vicinity were demolished, notably the former Rosenbaum Clothier and Hatter building at 7th and Penn in the 1970s.

Below: Southeast corner of 7th and Penn Streets, early 1970s.

Leave A Comment