John Nolen (1869–1937) was the first American to identify himself exclusively as a town and city planner.

Nolen was orphaned as a child and placed in Girard College. After he graduated first in his class in 1884, he worked as a grocery clerk and secretary to the Girard Estate Trust Fund before enrolling in the Wharton School of Finance and Economics at the University of Pennsylvania in 1891. Nolen earned a Ph.B. in 1893, and for the next ten years worked as secretary of the American Society for the Extension of University Teaching. He married Barbara Schatte in 1896.

In 1903 Nolen sold his house and used the money to enroll in the newly established Harvard School of Landscape Architecture, under the famed instructors Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Arthur Shurtleff, and B.M. Watson. He received an A.M. in 1905 from Harvard. He established an office in Cambridge, Massachusetts where he and his associates branched out into city planning, as well as landscape architecture. Nolen was a frequent lecturer on city and town planning, and was active in many professional organizations.

Below: John Nolen.

Over the course of his career, Nolen and his firm completed more than four hundred projects, including comprehensive plans for more than twenty-five cities, across the United States. Like other progressive reformers of his era, Nolen looked to Europe for models to structure the rapid urbanization defining modern life into more efficient and livable form. His books, including New Towns for Old: Achievements in Civic Improvement in Some American Small Towns and Neighborhoods promoted the new practice of city planning and were widely influential.

In 1909, John Nolen, at the invitation of the Civic Association of Reading, was engaged by private interests to replan the town of Reading. City planning in the USA was in its infancy around 1909 but it was successfully practiced in Germany. Wyomissing conformed to the German by laying out the suburb and separating factories from residences and providing green space for people.

J. Horace McFarland (1859 – 1948) from McAlisterville, Pennsylvania, a leading proponent of the “City Beautiful Movement” in the United States, got Nolen his commission and progressive factions within the city became his supporters.

Nolen wanted Reading’s Penn Square enhanced by a mall as long as the square with public buildings nearby.

Below: Intersection of Fifth and Penn looking North.

Below: Intersection of 4th and Penn looking East.

He also wanted a belt parkway around the city, thoroughfares widened and extended, railroad crossings eliminated, new bridges built crossing the Schuylkill River, playgrounds in every neighborhood, overhead wires put underground, a sewer system completed, and housing for workers improved. His suggestion to employers to build homes for workers in the country was a harbinger of the many industrial, country-like towns the federal government was to build for workers during World Wars I and II.

The idea of a beltline, eighteen miles in circumference, for pedestrians and vehicles, similar to Vienna’s Ringstrasse, was the most innovative element in his plan. At that time five-sixths of this proposed beltway already existed in the form of country roads. Thus all that was needed was to merely connect the pieces of road, and then widen and improve according to some appropriate plan. The result would be a beltway or boulevard with an average width of 200 feet or more. It would have been eighteen miles in length and would have traveled through a rich variety of rolling country. The enhancement of real estate values along the line of the beltway would have been so great that abutting property owners could have afforded to donate the land required, so that the city and county would have only the expense of constructing and planting. It was John Nolen’s opinion that it would not only be cheaper, but also better and more interesting, to give the boulevard a somewhat different treatment in different parts, provided that it affords continuous drives, walks, and riding paths, that it is attractive throughout its course, protected from unsightly things, and in some degree separated from the ordinary sights and sounds of city life.

Below: General Plan for The Future City of Reading Pennsylvania.

Nolen’s task in Reading in 1909 was staggering. This was a built-up, congested and constricted city of narrow alleys and streets, locked within a binding grid, with almost no restrictions on its laissez-faire development. The closer one came to the center of the city, the more destitute conditions became. Wealthier citizens, living in well-groomed wards farther away, were indifferent to the needs of workers and their children. Among these affluent people were landlords who were well aware “that overcrowding increased land values.”

Reading was a grimy, smoke-belching, industrial city whose economy was controlled by owners and managers of “manufacturing plants …handling coal iron, furniture, hardware, brewery, car and heavy machine products.” These forces, in obedience to the wishes of the Reading Railroad, the city’s largest employer, and with the cooperation of political parties, including the Socialist (whose members distrusted city officials) brought Nolen’s plan down. Through their united efforts, on November 8, 1910, they voted against a loan to implement Nolen’s proposals, many of which had been watered down. While Nolen had other failures and while most of his plans were only partially completed, his defeat at Reading was one of his greatest disappointments.

In fairness to Reading, the city adopted many of Nolen’s proposals in subsequent years, some of them after consultation with him.

John Nolen was a visionary ahead of his times. Nolen advocated for cities to grow and expand, always with guidelines and goals in mind, developing in synchronization with its population growth instead of before its time, or, even worse, after the chance for planning had passed. Nolen warned that if planning Reading’s growth were to be done haphazardly, it would lose many of the advantages that nature had gifted it. He admonished the city for having a plan that was “not thoughtful, but on the contrary, ignorant and wasteful.” One can only wonder what Reading would have looked like today had city planners listened to John Nolen and prevented builders from building row homes, widened city streets and provided more parks and green space for people.

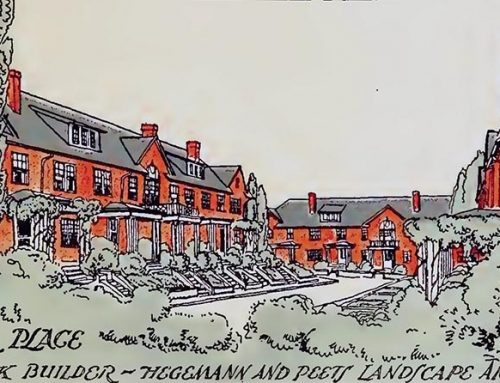

Nolen’s plan for a paradise was realized west of Reading. Spanning the streetcar and automobile eras, Wyomissing Park (1917-21), a garden village first planned by Werner Hegemann and Elbert Peets, with the assistance of Joseph Hudnut, and later reenvisioned by John Nolen, was situated west of Reading, Though neither plan was fully realized, Nolen’s contribution promised “one of North Americas most elegantly planned suburbs” featuring some of Nolen’s most beautifully designed residential streets.

The children of Reading appear to understand the place and need of play better than their elders. In the early part of the summer of 1910 the Reading local paper offered to print brief letters from the children themselves on the subject of playgrounds. These are some of the typical ones:

SOME LETTERS OF THE CHILDREN OF READING ON PLAYGROUNDS

Leave A Comment