The first industries in Muhlenberg Township developed in Temple. The Mount Laurel Furnace for the manufacture of iron began in 1836 on Mount Laurel Road. Built in 1836 by John Bertolet, Mayberry Bertolet and Francis Palm, Mount Laurel typified the small, standard charcoal operation. All the materials necessary to operate the furnace, with one exception, were gathered in the vicinity of Mount Laurel Road which meanders through the green hills known as the Irish Mountains.

Charcoal, produced in cone-shaped piles from the timber of the Irish Mountains, provided the fuel to smelt the iron ore. Limestone found throughout the fields and outcroppings served as the metallurgical flux. Water power to operate the bellows necessary to force air into the fire to make it hotter was obtained from the Laurel Run located directly in front of the furnace. The missing ingredient, iron ore, came from Cornwall and Morgantown.

Mount Laurel Furnace, like many other small operations, experienced financial panics and changed hands often or was reincorporated under different names. The Clymer brothers, William H. Clymer and Edward M. Clymer, purchased the furnace in 1846.

In 1860 William and his brother purchased the old Oley Charcoal Furnace near Friedensburg, one of the oldest charcoal furnaces in the United States, and commenced mining iron ore extensively. He and his brother also invested money in the Leesport Furnace.

In 1867, in a separate and independent endeavor, William Clymer also built a modern anthracite furnace in Temple, westward on the same road as the Mount Laurel Furnace, on the lower slope of the Irish Mountains, near the tracks of the East Penn Railroad. William H. Clymer & Company operated this furnace until 1870 when it was reorganized as the Temple Iron Company with William H. Clymer as president. Two of Clymer’s brothers, Daniel and Edward, held leadership positions with the East Penn Railroad and were useful in providing a link between the railroad and the Temple Iron Company. Later, the East Penn Railroad was leased to the Philadelphia and Reading.

Below: Location of Mount Laurel Furnace and Temple Iron Company form Berks County Atlas of 1876.

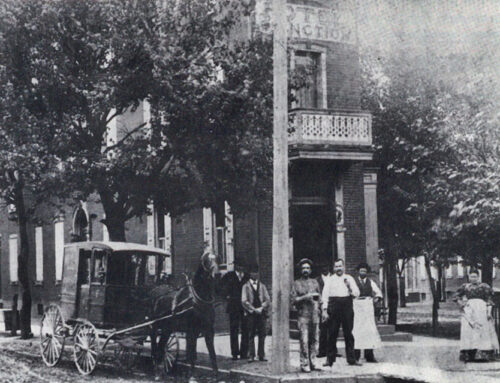

Below: William Clymer lived in the Mansion House, located at 1815 Mount Laurel Road, for thirty-five years. The Mansion House, remodeled into modern apartments today, was the biggest house around and contained living space for several families. Large rooms with high ceilings occupied the first floor, and although there were different families living here, the interior of the house had not been destroyed to create private apartments and entrances. Next to the Mansion House was the lower pond and a frame, woodland cottage. Unfortunately, the pond, created by the run-off from the Mt. Laurel spring, was drained in later years due to the drowning death of a little boy.

About 1880 the Clymer brothers had the Mt. Laurel Furnace changed from a charcoal to an anthracite furnace, and a railroad, one and a half miles in length, was built from the East Pennsylvania railroad at Temple to the furnace. After these improvements were made the brothers organized the Clymer Iron Company, a corporation which included in its operations the Mt. Laurel Furnace, Oley Furnace, extensive limestone quarries at Bower’s Station, iron ore mines near Pricetown, and a number of mines along the East Pennsylvania railroad.

Below: The Clymer Iron Company office building, 1820 Mount Laurel Road, survives today across the street from the Mansion House. It is hard to recognize because of extensive renovations, but its original brick, box-like structure is still discernible. The four hips of the roof meet at a center chimney pot of yellow ceramic ware which is part of the original architecture. Before it became a private residence, the center of the building contained a massive safe.

The Clymer Iron Company corporation, of which William H. Clymer was president, was entirely independent of the Temple Iron Company, of which he was also the president. About a year before his death Mr. Clymer resigned the presidency of the Clymer Iron Company, on account of ill health and was succeeded by his brother, Hiester Clymer. He, however, retained the presidency of the First National Bank of Reading, which he held from 1876 until his death, and the presidency of the Temple Iron Company. He removed with his family to Reading, PA, in September, 1882, and died there July 26, 1883. He had a large acquaintance and was greatly respected for his sterling character; was a man of excellent judgment. and his advice was frequently sought upon many important matters. He was brought up an Episcopalian and was a member of Christ Church, Reading, at the time of his death.

The youngest brother of William Hiester Clymer, George E. Clymer, was the last of the family to own the Mount Laurel Furnace. After graduating from Princeton in 1849, he joined his brothers in the iron operation for a short time. Then he left to survey railroads out West and to fight in the Civil War. Later, he worked for the Swift Iron and Steel Works of Newport, Kentucky, which was owned by his father-in-law. In 1884 he returned to Reading where his interest in the iron industry surfaced again. With the death of his two brothers, William and Hiester, George Clymer was able to purchase the Mountain Laurel Furnace from the estate and operated the site until 1892 when the furnace was dismantled.

Below: Historical Marker at former location of Mount Laurel Furnace.

As members of the Clymer family expired, new interests and new management operated the Temple Iron Company under a special charter granted by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1873. In 1898 the elasticity of this charter was discovered by George Baer, Reading attorney and industrialist, and some of his friends from the powerful financial institution of J. P. Morgan and Co.

In 1900, the Temple Iron Company reorganized, with capital of $30,000,000, for the purpose of operating anthracite coal mines. George Baer, who became president of the reorganized Reading Railroad in 1901, used the liberalism of the Temple charter to buy up many coal companies in the anthracite region at a time when railroads were forbidden by law to own or operate coal mines whose products they hauled. Then he appointed presidents of various railroads to positions of trust on the board of the Temple Iron Company, thus effectively creating a monopoly over the rates and prices of coal as it was shipped from the Coal Regions to the seaboard. This scheme might have gone on for a long time had it not been for a workers’ strike which drew national attention to the coal mines.

Below: The Temple Furnace and Depots looking Northward along Mount Laurel Road, Temple, Muhlenberg Township. The complex was situated on the north side of Mt. Laurel Road and on the east side of the East Pennsylvania Railroad tracks. Beneath the tracks was a culvert that permitted vehicular traffic to freely traverse Mount Laurel Road, part of which is visible on the lower right. The railroad spanned the road on a bridge about 25 feet overhead, but that bridge had been removed in the 1970s. The old railbed was turned into a community trail and is now part of Muhlenberg Township’s Rail Trail.

In the spring of 1902 miners in the Pennsylvania coal fields went on strike demanding a nine-hour working day, higher wages and, most importantly, recognition of the United Mine Workers as their collective bargaining agent. The strike dragged on, and as winter approached, it looked like there would be severe coal shortages in the cities of the Northeast. President Theodore Roosevelt finally intervened and forced the miners and company owners into arbitration and eventually a settlement.

Although the miners did receive increased wages and a nine-hour day, the mine owners refused to bargain with the United Mine Workers. One unexpected result of the strike was the exposure of the Coal Trust, that special group of railroads which owned the mines as well as the method of moving the coal to market. George Baer and the Temple Iron Company turned out to be one of the biggest violators of the Sherman Antitrust Law passed to protect the American consumer from monopolies.

The case traveled all the way to the Supreme Court, and, in 1913, the Court ordered the company to break up and sell off its holdings. At the time of its dissolution in 1914, six anthracite railroads controlled the Temple Iron Company and owned the following: Northwest Coal Company, Edgerton Coal Company, Sterrick Creek Coal Company, Babylon Coal Company, Mount Lookout Coal Company, Forty Fort Coal Company and the Lackawanna Coal Company. It’s worth was estimated in the millions of dollars. The pig iron industry which employed approximately 160 hands in Temple turned out to be just a tiny slice of the industrial pie.

The Temple Iron Company ceased operating on April 10, 1924. On September 3, 1925, at a meeting with stockholders, formal action was taken to dissolve the Temple Iron Company. The U.S supreme court having decided that it constituted a monopoly.

Devoid of its former influence and deserted by its former powerful associates the plant fell back to its former position in the industrial world. It became evident that it would soon go the way of other industries which had been outclassed and outstripped by the larger and more labor-saving plants.

The Temple furnace was sold for a junk price in July of 1928 marking the end of one of Berks County’s historic industrial plants. For many years it was one of the landmarks of the East Penn Valley, its stacks and its cinder dump serving as a sort of a lighthouse to nighttime travelers.

After more than a half century of usefulness, the old Temple Iron Company’s plant was dismantled. On August 22, 1928, dynamite was used to raze one of the giant stacks of the mill. Four blasts were necessary before the sturdy steel stack gave in and toppled over a mass of twisted wreckage.

Below: Demolition of the Temple Furnace.

For a time the Temple plant was associated with kings and giants of the industrial world. In the hey-day of its glory it was the center of that powerful industrial and commercial group commonly known as the anthracite coal trust. Its sudden rise to a position of power and influence and its fall from the same a little over a decade later constitute one of the most interesting chapters in Berks County’s industrial history. Several rows of company homes in Temple and the ironmaster’s house at 1139 Mount Laurel Road remain as material proof of the furnace’s existence.