In the 1930s Reading, Pennsylvania, was a medium-sized city of 111,000 inhabitants. As the seat of Berks County, Reading was the social, political, and economic focus for the predominantly agricultural communities that surrounded it. It was also a faultless embodiment of Main Street, U.S.A. – that iconic place Architectural Forum described as “big enough to have most of the features and most of the problems found on Main Streets the country over, small enough to retain the small-town atmosphere in which well over half the Nation’s retail business is done.” Because of its proximity to Philadelphia and New York, both easily accessible by train, Reading was subject to big-city cultural influences that shaped its tastes and consumption habits. To this end, the local newspaper, the Reading Eagle, regularly reported on the art, culture, and lifestyles of both cities. Because of its political importance as the Berks County seat and its distinct historical heritage derived from its original Pennsylvania German settlers, Reading also possessed a deep-rooted local pride and a thriving middle-class booster culture that stressed its independence and self-sufficiency as “a city lacking nothing in the essentials of community life.” The town had a long tradition of civic organizing, from the City Beautiful to the Christian Temperance movements, and this localism continued through the Depression with, according to the Chamber of Commerce, “a purposeful community spirit that never falters in the face of difficult civic problems.” It is not surprising, then, that when the Democratic nominee for governor campaigned in Reading in 1934, he promised “a government by Main Street instead of Wall Street” to emphasize the town’s autonomy and its belief in its ability to manage its own affairs.

At its economic base, Reading was factory-dependent and, like many such towns in the 1930s, this “home of progressive industry” was hit hard by the Depression, experiencing labor unrest and widespread unemployment. While Reading possessed a variety of industries, including over forty hosiery and textile mills, its largest employers were allied with the building trades-manufacturers of hardware and fittings, nuts and bolts, terra-cotta, and bricks. This meant that Reading would feel most keenly the building industry’s post-1929 downward spiral, especially in the shrinking purchasing power and decreased spending of its under and unemployed, be they factory workers, contractors, or architects. By 1932 some local unemployed men had built a large shantytown along the Schuylkill River with semipermanent shacks, garden plots, and rabbit hutches. Two years later this “Depressionville” was still in existence, with many of its occupants on federal relief.

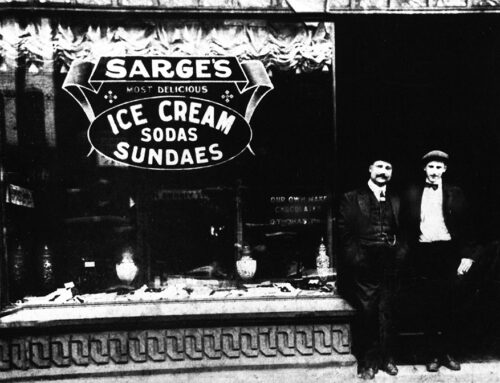

The Depression also left its mark on Reading’s principal commercial corridor, densely built Penn Street, which stretched east to west for nearly a mile from the foot of Mount Penn to the banks of the Schuylkill River. Where Penn crossed Fifth Street, it became Penn Square, the anchor of the downtown core. Though it had been the site of the county courthouse in the eighteenth century, Penn Square had long since become the commercial crossroads of Reading and Berks County, serving a trading area with an eighteen-mile radius and a population of 300,000. In the 1930s it was experiencing the same fiscal and physical ills that plagued so many Main Streets at the time: a rotation of stores and other establishments into and out of business and a cycle of storefront and building occupancy and abandonment. In Reading the impact of the economic downturn was readily apparent by 1931 as signs announcing bankruptcies, expired leases, and merchandise reductions were gradually plastered over Penn Street shop fronts. Along the north side of the 600 block, seven out of fifteen stores had been forced out of business, including the well-established Victor Jewelry, whose “Pay Me Pay Day” sales slogan, spelled out on a two-story flashing marquee, must have seemed to Reading’s jobless a bitter reminder of more prosperous times. Nearby, Keystone Meat announced that it would “redeem unemployment vouchers” presented by customers in lieu of cash payment, more accurately reflecting current conditions.

Below: Aerial view of Reading, Pennsylvania. In the 1930s Reading had a densely built downtown focused on the blocks surrounding Penn Square, at the intersection of Penn and Fifth streets. Penn Square served as the commercial center of the city and surrounding Berks County.

Below: The 600 block of Penn Street, circa 1932. By the early 1930s, Penn Street was feeling the impact of the economic downturn, evident in the vacant storefronts and bankruptcy signs typical of the early years of the Depression.

Equally bitter to struggling Reading merchants must have been watching the national chains thrive, apparently at their expense, in what had become an all too familiar retail battle between insider and outsider. The depth of this conflict was apparent in the reopening of the locally owned B&J Saylor food store at Fourth and Penn streets after a disastrous fire in 1933. The building, which Saylor’s had occupied since 1866, was a modest brick structure that had been gently modernized. Stripped of its decorative cornice and window surrounds, it created an appropriate stylistic balance for Reading’s self-described “oldest and most modern food establishment.” The advertisements Saylor’s placed in the Reading Eagle to announce its reopening were anything but balanced, as the store deliberately set itself apart from its chain rivals, claiming that it was “a distinctly Reading Institution,” which paid local taxes, supported local charities, employed local workers, and sold local products. But Saylor’s went even further in explicitly rejecting the chains, which were described as “larger and more powerful business aggregations.” It defended its traditional full-service approach to retail with unmistakable anti-chain rhetoric that would have likely resonated with Reading’s citizens during the Depression: “Saylor’s never approved of the self-service idea … the idea that labor should be eliminated from business as a matter of economy. If we are to live on automats, make this an all machine age and put everyone on doles, we better bust civilization or give it all to a few and be done with it.”

Though Saylor’s successfully fought off chain competition, for most local merchants such efforts were largely fruitless in the face of chain expansion as the Depression wore on. In a single retail category, for example, chain five-and-dimes like Woolworth’s, Kresge’s, and McCrory’s expanded their market share to a commanding 89 percent of all variety store business in Reading, with the five remaining independents attempting to stay open on the leftover 11 percent. While this disproportion was due in part to the low prices the chains offered, it was also due to the ambitious store modernization programs the chains undertook, keeping their units up-to-date as a way of stimulating sales during the economic downturn. In Reading the W.T. Grant dime/department store completely remodeled its nineteenth-century commercial palazzo on Penn Square. The sole occupant of its building during the Depression, it demolished the top floor and faced the remaining stories in a streamlined veneer of two-tone porcelain enamel veneer that wrapped around the corner in a seamless curve emphasized by a stainless steel canopy above the storefronts. Other chains seized the opportunity presented by Penn Street’s apparent retail decline to seek out better locations, larger quarters, or more advantageous leasing terms, often moving in and modernizing after the failure of longtime local establishments. The Federal Furniture Store at 625 Penn had no sooner shut its doors than Thom McAn Shoes installed one of its 1932 “Model F” storefronts. When the Sondheim’s clothing store at 700 Penn finally went under, A.S. Beck Shoes took over the street level of this Victorian Gothic structure and modernized it, despite the chain’s usual flamboyance, with a restrained design in porcelain enamel by New York architect Horace Ginsbern.

Below: In Reading the W.T. Grant dime/department store completely remodeled its nineteenth-century commercial palazzo on Penn Square.

Below: The corner of Penn and Seventh streets. As on so many Main Streets, chain retailers expanded aggressively on Penn Street in the 1930s. Here, A.S. Beck Shoes took over a prime corner location after a locally owned clothing store went out of business.

As detrimental as the proliferation of the chains might have been to the stability of Penn Street’s independent merchants during the Depression, the high mortality rate of local stores could not be ascribed solely to the perceived incursion of anonymous corporate outsiders. As in other American cities, Reading’s real estate industry and property owners had to share the blame, having produced an oversupply of business frontage and retail space. Though much of this seems to have occurred during the boom years of the 1920s, it continued into the Depression as landlords attempted to restore properties to profitability the easiest way they could-by creating retail space. In 1937 the Mansion House Motel, where important visitors to Reading had stayed for nearly a century, was torn down and replaced by a streamlined taxpayer with three retail units, each occupied by a chain. When the stalwart Penn National Bank & Trust Company folded after nearly sixty years in business, its Georgian-style 1920s headquarters at Eighth and Penn were summarily modernized for retail leasing. The banking hall was divided into two store spaces with deep vestibules, off-center curving displays, and glass-block panels illuminating the second floor. Though faced in structural glass to the height of the third-story stringcourse, the building’s historical details were intact above-its balusters, oculus, and raking cornice contrasting sharply with the deliberate modernity of the facades below. By 1937 there was nothing remarkable about the storefronts of the former bank-similar ones could be found throughout the United States, and nearly identical ones were already in place on Penn Street itself (Sach’s at 714, Gilman’s at 660, Martin’s at 658).

Below: The corner of Penn and Eighth streets in 1938. During the Depression, institutional failure frequently created retail opportunities. After the Penn National Bank & Trust Company folded in 1937, its building was divided and modernized. The storefronts featured structural glass, glass blocks, and extruded aluminum.

Throughout the 1930s Reading’s retail shuffle was closely watched by a number of commercial organizations dedicated to promoting the city’s business affairs. Chief among them were the Board of Trade, founded in 1881 with a mission of “fostering, protecting, and advancing the interests of the business community,” and the Merchant’s Bureau, committed to keeping retailers “working harmoniously” in the city’s commercial interests. Both organizations recognized the immediate impact that the Depression was having on the local economy through direct industrial downturns and trickle-down effects like the reduced purchasing power of consumers. In early October 1934, they joined with individual businesses to celebrate the opening of the Union National Bank (a new institution that emerged out of the Depression-induced failure of three local banks) and what it portended for Reading’s future: “This new bank brings happiness to Reading… gives additional support to retail and industrial development already on the upgrade… the pulse of business will be quickened… improvements can be made.” As the Reading Eagle noted, it was the first time since March 1933 that the city’s financial institutions were in full operation with “no closed or restricted banks standing as a barrier to business.” By that fall the Reading business community had already been actively working to remove any other remaining barriers to business by embracing the diverse recovery programs of the New Deal. And just as the Union National Bank was preparing to open its doors to community lending, the blue eagle emblem of the National Recovery Administration, which the Chamber of Commerce had been distributing since July, was about to be supplanted by the black house logo of the Better Housing Program (BHP).

In Reading, as in towns across the United States, the passage of the National Housing Act and the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration were front-page news in the summer of 1934, especially when FHA head James Moffett explained that the goal of the Modernization Credit Plan was to stimulate building activity in order to prime the pump for broader economic recovery. Given the importance of the building industry, specifically building material manufacturing, to Reading’s economic health, the community must have been closely following this particular recovery program. As early as July, local banks were already publicizing their commitment to extend credit to “worthy manufacturers and merchants” in order for “business to forge ahead in this community.” Simultaneously, local department stores had already begun to promote “modernization” as a marketing catchword. Pomeroy’s, at Sixth and Penn streets, even sponsored a contest for the best essay on the theme of “Why I like the modernized third floor,” with the winner getting an all-expenses paid trip to the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago. With such early support from the business community, it is not surprising that Reading was one of the first communities in Pennsylvania to organize a local BHP to promote building modernization.

The organization of the Reading and Berks County BHP committee began in October when regional FHA officials met with Reading mayor Heber Ermentrout, who soon announced that Frederick H. Dechant would serve as chairman of the Reading committee. Dechant was a civil engineer and a partner with his architect brother in a well-known Reading design firm founded by their father. In his initial comments to the press, Dechant echoed numerous FHA publicity statements, carefully explaining how the new program would help end five years of stagnant building activity, maintain and improve property values, provide local employment, and get money into circulation. Claiming that it was “very practical” and “prompted by nothing short of necessity,” Dechant optimistically concluded that “everyone will welcome the campaign we are organizing locally.” He lost no time putting that campaign together along the lines recommended by the FHA: as assistant director, he named Carl Harbster, a sales manager in the wholesale lumber industry; as the head of specialized industry committees, he named Robert Millard, a building material and electrical appliances salesmen, and H. Raymond Hackman, an architect who was also superintendent of school buildings for the Reading district; as head of the women’s committee, he named the wife of Allyn C. Taylor, manager of the Reading Gas Company and a former president of the Reading Rotary Club; to head the field campaign, he named Arthur Chafey, a former sales manager and field supervisor for the Atlantic Refining Company. With his team in place and the campaign headquarters prominently installed in the Ganster Building at Fifth and Walnut streets, just off Penn Square, Dechant launched the Reading modernization drive with an “electrical show” and a parade in late October.

Even before Dechant’s BHP committee began its work, the MCP was already having a local effect. City building inspector J. Earl Hickman found that the value of permits for repairs and alterations for August 1934 were more than double what they had been for the same period in 1933, jumping from $9,000 to $20,000. Hoping to further encourage this trend, and as a sign of its cooperation with the federal effort, Reading announced that it would exempt building improvements from higher property tax assessments-a decision that the FHA had been actively promoting on the municipal level. Also in anticipation of the modernization drive, city assessor Walter Ringler compiled a report from existing tax records on the number and types of buildings within Reading’s corporate limits, including business, industrial, residential, and institutional structures. This report-which found 2,413 businesses occupying 2,173 buildings and 5,313 apartments occupying 1,827 buildings-was essential to the building-by-building canvass that took place in early November to determine the extent of building modernization required in Reading. As the FHA repeatedly asserted in its promotional materials, the community canvass was to be the heart of the modernization campaign, and it was no different in Reading. Several weeks before it was scheduled to begin, Mayor Ermentrout requested that local residents cooperate fully since “what is to be done is in the line of a community welfare project.” As the date of the survey drew near, he issued an official proclamation: “In this worthy and vital movement, made possible by the National Housing Act, we urge that every owner of real property act at once,” declaring finally that “the opportunity and challenge are yours.”

The canvass began on the first Monday in November with one hundred workers covering the entire city, which had been divided into geographic field districts. These men and women were not volunteers but were paid from state and federal relief funds and drawn from local relief rolls by employment coordinator Paul Kintzer. They received several weeks of training at the local YMCA, including technical instructions and inspirational pep talks, with Chairman Dechant reminding them that only “prompt action will arrest the processes of obsolescence.” Once they were in the field, they canvassed all properties within a three-mile radius of Penn Square, including not only the city, but its inner suburbs as well. The canvassers’ goal was to ascertain whether property owners were contemplating repairs and improvements, the nature and extent of contemplated repairs and improvements, and the possibility and/or necessity of additional repairs and improvements to the property. They also attempted to explain how property owners might prioritize the work, recommending which repairs and improvements could be undertaken at once with a minimum of preparation, thus getting Reading’s building workers back on the job as quickly as possible.

Back at the campaign headquarters, Dechant and his staff “poured over statistics compiled by the first group of canvassers” and used the information collected to prepare cost estimates of modernization and repair work, and to provide leads for follow-up calls made by canvassers and contractors. Within one week the canvass had begun to show results, as sixteen repair permits were issued as a direct result of the BHP. Dechant, meanwhile, was doing all he could to maintain high public interest in the campaign as the canvass continued. He released regular statements describing the value of building modernization, as, for example, in the case of an apartment building that was 30 percent occupied before modernization and 75 percent occupied after modernization or a vacant store building that was divided into two retail spaces and immediately leased. Though Dechant was supposedly describing local examples, they tended to lack specifics-a strange omission in a city that frequently published exact addresses for which building permits had been issued-indicating that they were more likely taken from promotional materials prepared by the FHA Publicity Department. In any event, the strategy worked. By the spring of 1935, Reading’s two leading financial institutions had extended over $62,000 worth of modernization credit representing nearly $350,000 of private capital unlocked and modernization work undertaken.

Assuming, as the FHA did, that only half this amount was spent on commercial modernization, store improvement expenditures in Reading may have potentially reached between $31,000 and $125,000. With a modest storefront costing between $1,000 and $1,500 in the 1930s, more than a few Penn Street merchants were modernizing their establishments after 1935. And nowhere was this more apparent than with stores in and around Penn Square.

These modernized storefronts, and the newness they embodied, had the same economic and architectural consequences in Reading as they did in towns across the United States: economic because they attracted the attention of customers and tenants; architectural because, as modernization advocates claimed, a single modernized store would force competing merchants to respond in kind, seeking through modernization to convince a skeptical public that their establishments were equally up-to-date. When A&P Supermarkets modernized an abandoned taxpayer at 806-10 Penn Street and opened a combination grocery with an in-house butcher, it posed a serious threat to the independent Keystone Meats just four doors away. This threat was obviously economic in nature, based on A&P’s low prices and retail conveniences, which the company stressed in newspaper advertisements that were generally twice as large as those of its local competitors. Keystone’s response, however, was architectural. It modernized with a simple glass-and-aluminum facade reminiscent of A&P’s own standardized front.

Below: The 800 block of Penn Street circa 1935. After chain retailer A&P Supermarkets took over an abandoned taxpayer on Penn Street, local merchant Keystone Meats modernized its storefront, four doors away, as a means of keeping up with the competition. The A&P is visible at the far right of this image.

Below: The 800 block of Penn Street circa 1960s.

The pressure to modernize was not predicated solely on direct competition, however, since, as the FHA argued, the average Main Street merchant was “competing for the customers’ dollars, not only with the other merchants in your line of business, but with all merchants in all lines of business.” In Reading businesses that had operated successfully for years felt compelled to modernize in the 1930s. At the commercial crossroads of Penn and Fifth streets, the Crystal Restaurant had occupied the same site since the 1890s and the same building with the same storefront since around 1905. Nonetheless, in the late 1930s, though its only direct competition was a small lunch counter, the Crystal modernized, replacing its cast-iron and leaded-glass street-level facade with a sleek molded-steel front possessing an off-center entrance, rounded bulkheads, and neon signs, but given a distinctive note by its use of mirrored panels. When space became available two doors down, the Crystal expanded its operations, opening a bar (after the 1933 repeal of Prohibition) with a glass-and-metal storefront notable for its gaping bull’s-eye window. That space had been vacated by Tri-Plex Shoes, a longtime tenant who moved across the street into a building occupied until the Depression by the venerable dry goods store Kline, Eppihimer & Co, in business for over seventy years and regarded as one of the most “metropolitan establishments in Reading.” All traces of Kline, Eppihimer were erased from the street-level frontage by a flashy modernization that included banded letters and speed lines reminiscent of Raymond Hood’s McGraw Hill Building. These motifs were increasingly familiar around Penn Square and on Main Streets across the United States as a small-scale modern vernacular became commonplace.

Below: The 500 block of Penn Street circa 1930. The pressure to modernize was felt by many merchants in the 1930s, even when there was no direct retail competition occupying adjacent frontage. By the end of the decade, modernization would almost entirely transform this block at Reading’s commercial crossroads. The Crystal Restaurant is at the far right; Tri-Plex Shoes occupies the storefront two doors to the left.

Below: The 500 block of Penn Street modernized: the Crystal Restaurant and the Crystal Bar both have streamlined storefronts of the most up-to-date materials and forms.

Despite similarities in form, materials, and recognizable motifs, each modernized storefront was unique, the product of a singular coordination of merchant, architect, contractor, and manufacturer operating under the auspices of the federal government with the assistance of the local chamber of commerce. One such successful coordination occurred in Reading when merchant Ferruccio A. Iacone, architect Elmer Adams, and contractors Paul and Jasper Kase of the J.M. Kase Glass Company modernized a men’s clothing store at 519-21 Penn Street that occupied the street-level of a four-story nineteenth-century building. Iacone was an independent merchant who, in a reversal of retail expectations in the 1930s, took over the commercial lease of a space that was vacated by a chain shoe store. Adams was a Berks County native who had been in Reading since he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1929. Though he spent several years as a draftsman in some of Reading’s leading firms, including that of local BHP chairman Frederick Dechant, by 1932 he had entered into a partnership with a fellow Penn graduate. When his partner took a job with the U.S. Commerce Department in Washington in 1934, Adams set up as a solo practitioner. Like so many other young architects in the Depression, he seems to have dealt with the slowing of building activity by directing his skills into other channels, executing a series of watercolor renderings of Reading landmarks and scenes of local interest, presumably for sale. Once the plans he prepared for Iacone were approved, Adams submitted them to J.M. Kase. Kase Glass was an art glass studio founded in 1888 that executed a number of important commissions in and around Reading, notably the windows in the Council Chamber of the Reading City Hall, completed just before the stock market crash in 1929. As specialty stained-glass work fell off during the Depression, Kase increasingly turned to commercial and small-scale glass installations that were more factory-produced than studio-designed. Following Adams’s material specifications, Kase placed an order with the Philadelphia Branch Sales Office of the Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company of Ohio for products from LOF’s Complete Storefront line. Within a few weeks, Iacone’s new storefront was installed on Penn Street.

Adams’s distinctly modern design for the storefront featured a single continuous display area with tall show windows that were flush with the street. These gave way to a T-shaped vestibule that was wide, deep, and au courant for a double-frontage men’s store in the 1930s. The vestibule allowed the compartmentalization of the window space into separate display areas for suits, haberdashery, and furnishings, and supposedly responded to the psychology of male consumers, who were thought to dislike street-side window-shopping. Such arrangements were well publicized in the modernization articles, portfolios, and advertisements that appeared regularly in the decade’s architecture journals as store re/design became increasingly important to American building culture. To complement this arrangement, Adams chose a rich but subdued color scheme of the type deemed appropriately masculine by retail experts, cladding his facade in Cadet Blue Vitrolite (structural glass) with Extrudalite (extruded aluminum) trim. The signboard above the entrance had inset letters in Cadet Blue Vitrolite and was fabricated of back-lit Vitrolux (color-fused tempered plate glass) used here in Suntan. This cosmetic-like shade indicates the degree to which the marketing of building materials during the Depression had absorbed the lessons of a female-inflected consumer culture. Two smaller badgelike signs flanked the store’s name, one with an Iacone “crest” and the other with the H. Kuppenheimer logo (a knight in chain mail) – a brand designation of high-quality menswear. Adams also specified Vitrolux for the top-lit ceiling panels of the vestibule and the display windows, which, like the signs above, glowed dramatically at night, giving the store what LOF would have called twenty-four-hour selling power. Though it was hardly a flamboyant composition, it would have been immediately noticeable to pedestrians leaving the numerous restaurants and movie theaters around Penn Square, especially because its modernism contrasted dramatically with the restrained stripped classicism of the Reading Trust Company building next door.

With its up-to-date styling, materials, and retail configuration, Iacone’s shop now possessed a distinct, if momentary, advantage in downtown Reading: distinct, because Adams’s design was notable for its modern, formal simplicity; momentary because the storefront’s newness would be rapidly overshadowed by the subsequent modernization of other shops on Penn Square. Indeed, even when the store was brand-new, it was already competing with the flashing neon of the modernized stores directly across the street. But such was the transitory nature of the commercial landscape in Reading, as the pressures of competitive modernization brought progressive visual change to Penn Street through seemingly endless iterations of the modern storefront. What was true of Penn Street was true of Main Streets across the United States. A relentless consumerism that grew more intense during the Great Depression produced these storefronts, and the federal government, concerned with stimulating the depressed building industry and the economy as a whole, underwrote them. Corporate manufacturers, desperate to maintain sales of their building materials, promoted them; and architects, anxiously seeking work and eagerly embracing modernism, designed them. Finally, as the observations of social commentators like Robert Lynd and Frederick Lewis Allen indicate, the American public received them, not merely as places to shop, but as a soothing visual panacea for a time of crisis. In other words, F. A. Iacone’s storefront was ubiquitous, quotidian, and absolutely emblematic of American culture in the 1930s.

The building that once housed Ferruccio Iacone’s men’s clothing store still stands on the 500 block of Penn Street, but the Vitrolite-Vitrolux-Extrudalite storefront designed by Elmer Adams and installed by the J.M. Kase Glass Company is no longer extant. In its place is a nondescript facade of fake brick and wood siding, an alteration that may have resulted from maintenance necessities, from the vagaries of commercial design, or from a weak nod toward the historic character of the building. The store itself is occupied by a combination pawn shop and check-cashing store, the sort of retail tenant that the Reading BHP in the 1930s would have considered a harbinger of commercial blight, especially in as prominent a location as Penn Square. Today 519 Penn Street-the storefront and the tenant-stands as an indicator of the changes that Reading’s commercial district has undergone in the decades since the New Deal effort to modernize Main Street came to a close at the start of World War II. If Reading was emblematic of Main Street, U.S.A., before the war, it remained so after the war. In 1939 the Chamber of Commerce declared proudly that “Reading can surely invite comparison with any city of its size or class in this country.” For better or worse, Reading’s recent history has borne out this statement.

The war effort that finally brought increased production and employment back to Reading’s factories and mills was undoubtedly a boon for downtown merchants. However, once the peacetime economy was in full swing in the years after 1945, Reading’s workers were no longer spending their paychecks exclusively in Penn Square. The decentralization that began before the war only intensified with the suburbanization of the postwar period in the form of interstates, subdivisions, shopping centers, and malls. As these spread across the United States, the predominance of the historic center gradually eroded in the 1950s and 1960s. In many cases, Main Street merchants-chains and independents alike-even facilitated the outward movement, hoping to profit from the suburbs in the same way they had once profited from downtown. Solomon Boscov was one such retailer, having opened his first “economy” dry goods store in Reading in 1917, at Ninth and Pike streets on the northern edge of downtown. By the 1930s it had expanded across three storefronts and was regarded as Reading’s leading discount department store. Though Boscov modernized this location in 1954, by the early 1960s the company had expanded beyond Reading’s commercial core, first to its inner suburbs and then to the rapidly developing townships beyond Berks County. When fire destroyed the original Ninth Street location in 1967, the company did not rebuild, and it abandoned downtown Reading for good.

At this time, it wasn’t only the retailers and householders who were decentralizing; industry was as well, with consequences just as debilitating for Main Street merchants and for downtowns as a whole. In Reading manufacturers who had been the city’s economic mainstay for decades, including the Reading Hardware & Butt Works and the Berkshire Knitting Mills, began to relocate or to shut down entirely, leaving Penn Square further drained of potential customers and surrounded by underutilized factories. As it had in the 1930s, the federal government once again offered downtown assistance. Now, instead of “modernization,” it was “urban renewal” that was put forth as the cure-all of the moment, especially after the introduction of the Model Cities Program in 1966.

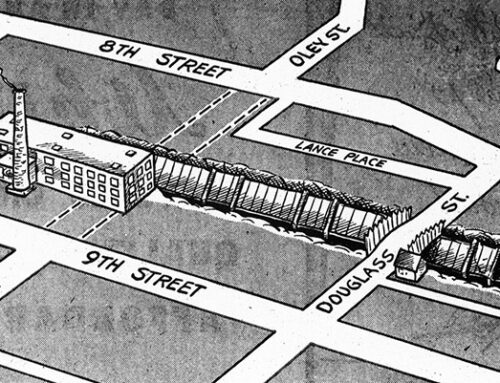

Below: Model Cities Program in 1966.

In many downtowns, however, urban renewal looked more like suburban imitation, and Reading was no exception. Six blocks northeast of Penn Square were slated for demolition, to be replaced by an enclosed shopping mall. Though the project never came to fruition, many buildings in the area were razed anyway, replaced by parking lots that did little to assist struggling merchants. In the early 1970s, the city tried a more modest suburban-style intervention, building an open-air pedestrian mall along the length of Penn Square. Featuring enlarged sidewalks, benches, lighting, brick pavers, concrete bollards, planted medians, and limited vehicular traffic, the Penn Square Mall was intended to function like an open-air shopping center, encouraging window-shopping and downtown strolling. But, like many pedestrianization schemes built in this period, the Penn Square Mall never produced the desired Gruen effect, and it was removed in 1993 to allow the reintroduction of buses on the Penn Street corridor.

Below: Architect’s rendering of Penn Mall envisioned in the early 1970’s.

Below: Penn Square Pedestrian Mall, 1970s.

Below: Aerial view of Penn Square Pedestrian Mall, 1970s.

By that time, Main Street’s increasingly dire predicament was once again a subject of intense debates at national and local levels as American cities and towns came to grips with the devastating dual legacies of suburbanization and urban renewal. Communities were forced to acknowledge that the golden era of Main Street had ended, and that it would never again be the nexus of social, civic, and commercial life that it was before World War II. But even as Main Street was confronting this reality, a new attitude emerged. Robert Venturi famously asked: “Is not Main Street almost alright?” and a generation of designers and developers eventually followed his lead. Critics of modern urban planning, such as Jane Jacobs and Kevin Lynch, championed the vitality of the street and the streetscape, proposing that commonplace activities and commonplace buildings all contributed to a unique definition of place that should be celebrated rather than bulldozed. This helped refocus attention on the traditional commercial core, spotlighting precisely those things that made Main Street so successful in its heyday: a concentration and diversity of everyday uses and an eclectic mix of building types and styles. Enhancing these characteristics became a critical part of the downtown revitalization strategies that emerged in the late twentieth century and that are still ongoing at the start of the twenty-first.

In Reading the city’s first historic district, listed on the National Register in 1980, centered on the blocks in and around Penn Square, including some that had been threatened with demolition only a few years before. Now, however, Penn Square was lauded for its nearly intact fabric of typical commercial buildings featuring styles “from federal to art moderne” – all reflecting the city’s “historic regional strength in retailing.” A decade later merchants and property owners formed a Downtown Improvement District (DID) to stimulate commercial activity in Penn Square. With funding from special assessments, the Reading DID sponsors beautification programs (including painting murals, installing holiday lights, and upgrading street furniture); organizes street festivals, parades, and special shopping days; and trains “district ambassadors,” who provide information about downtown to locals and visitors alike. The DID also assists property owners in securing facade improvement grants through the Reading Community Development Department. None of these activities would have been out of place on Penn Street during the Great Depression.

In fact, what is so striking about efforts to revitalize Main Street today is how closely they resemble efforts to modernize Main Street in the 1930s. The buzzword may have changed, but the determination to fight commercial decline through architectural design, local boosterism, community organizing, and economic development is largely the same. These areas of engagement are the basis of the so-called Main Street approach currently advocated by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Though the trust is a nonprofit organization (albeit one chartered by Congress), it plays a sponsorship and promotional role analogous to that of the Federal Housing Administration during the New Deal. Through its Main Street Center, founded in 1980 after a scries of demonstration projects in the late 1970s, the trust provides technical assistance and support to over 1,200 member communities. While this number hardly rivals the 8,000-plus towns that participated in the FHA’s program, the trust’s sphere of influence is still considerable, since hundreds of additional communities subscribe to its general precepts through various public-private partnerships, as in Reading. In many respects, the National Trust’s goals for Main Street today are almost identical to the FHA’s in the Depression: that Main Street, however diminished, should retain its economic and cultural importance as a center of employment, as a contributor to the tax base, and as a locus of community pride.

If the two Main Street programs share similar goals and means, there is at least one crucial difference between them. In the midst of the social and economic crisis of the Depression, the FHA promoted the short-term, high-impact solution of building modernization, which utilized the most striking visual hallmarks of contemporary design. The National Trust, by contrast, favors incremental, long-term strategies within the context of historic preservation, which utilize the subtle design tactics of restoration and rehabilitation. In the trust’s view, Main Street’s successful revitalization is to be based on a vision of the past as embodied in its “traditional” commercial architecture. In the FHA’s view, Main Street’s successful modernization was to be based on a vision of the future as embodied in its “modern” commercial architecture. In both cases, the storefront is made to represent the aspirations of the district as a whole, with traditional forms embodying what the National Trust perceives as Main Street’s pre-WWII heyday and modern forms embodying what the FHA hoped would be Main Street’s post-Depression glory days. Of course, traditional and modern are relative terms, especially within the ephemeral landscape of American commerce, and sometime between 1943 when the FHA program ended and 1977 when the National Trust program began, Main Street’s future started to look an awful lot like its past.

Today there are federally approved standards and guidelines for preserving the historic modernized storefronts of the 1930s. They have apparently “gained significance over time,” though they were never intended to endure much beyond the Great Depression-as virtual architectural consumables, it was understood that they would become obsolete as storefront trends changed. But at a critical moment during the Depression, these storefronts provided an optimistic glimpse of a prosperous tomorrow, one seemingly guaranteed by the machine-age luster of chrome, neon, and glass. Encountering these modernized storefronts seven decades later, we realize that the machine age has ended, that the luster has dulled, and that a prosperous tomorrow is far from certain. But in the preservation of these storefronts, we may also realize something else, something that architects, merchants, consumers, and New Dealers all understood in the 1930s: that Main Street is more significant than just a place to shop.

Leave A Comment